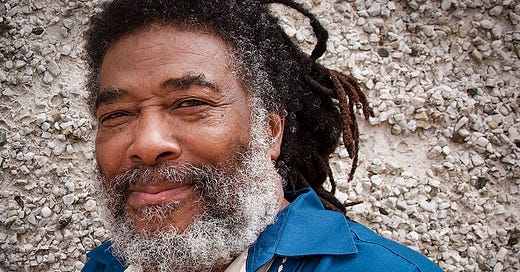

Photo by R.I. Sutherland-Cohen

Wadada Leo Smith is a composer, improviser and visual artist. Born in Leland, Mississippi, Smith has been composing music for more than 70 years, starting with his first piece at age 12. In the 60s, he joined the AACM and formed the trio Creative Construction Company (or CCC) with saxophonist Anthony Braxton and violinist Leroy Jenkins. He participated in a number of landmark recordings associated with the AACM, including Braxton’s debut release 3 Compositions of New Jazz and Kalaprusha Maurice McIntyre’s Humility in the Light of the Creator. Smith has performed and recorded with a wide variety of musicians over the years, such as Marion Brown, Frank Lowe, John Zorn, Susie Ibarra, Spring Heel Jack, Deerhoof, and Pauline Oliveros. In the 90s, he formed a group with improvising guitarist Henry Kaiser called Yo Miles!, which reinterpreted music from Miles Davis’ 70s electric period alongside Smith’s own compositions. In 2012, he released Ten Freedom Summers, a 4-CD box set consisting of music composed over the course of 34 years; it was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Music. At age 83, Smith has shown no sign of slowing down. He’s released 15 albums this decade, and just a couple of months ago he released Defiant Life, his second duo album with pianist Vijay Iyer; the two of them will be performing at Constellation in Chicago on June 27.

Smith was the very first artist I interviewed at Big Ears Festival, and we met at his hotel on March 28, 2025. As we took the elevator up to his room, a man asked us if we were here for the festival. Smith smiled and nodded, not mentioning that he was performing at said festival five times. That sense of humility is something everyone who has met Smith can speak to, myself included. He was incredibly generous with his time, talking for nearly 80 minutes even though lord knows he had plenty of work to do that weekend. We talked about composing his first piece at 12, his experiences in Paris, working with Brigitte Fontaine, the miracles he experienced on the Hajj, and so much more.

Special thanks to Ann Braithwaite for putting this interview together, and to The Wire for making it possible for me to go to Big Ears. You can read my coverage of the festival in the latest issue, 496.

Thank you so much for talking to me.

Where are you from?

Washington, DC, but I’ve been living in Chicago for two and a half years.

Oh, Chicago, ok.

I’m assuming you have pretty deep connections to Chicago.

Yeah, yeah. It was a home for me for a long time.

A big part of why I moved in the first place was knowing it’s one of the best places in the country for creative music.

That’s pretty true, yeah.

So a question I often ask people is what are your earliest musical memories?

Composing my first piece at 12.

What made you want to compose from such a young age?

Well, no one made me, but it’s the idea of how inspiration sets in on you. So I had the urge to compose, and I decided that I would just compose. My first piece was for three trumpets, and I made it specifically for three trumpets because I had two other friends who played trumpet. And, with myself, we could hear the music. So, after completing it, I immediately heard my first piece. Most people that compose music never do that. The urge to compose music, which I describe as a form of inspiration, and the desire to sit down and start composing without asking anybody, is also a well-known and important choice. I could have gone to my band director there and said “could you teach me how to compose?” I didn’t. And that particular move at the age of 12 has informed me for the last 70-something years.

Was wanting to play music with your friends something that motivated you to compose?

Yeah, because that meant that I could hear what the music was right away. Whereas usually people write pieces and then they put them on the shelf and they keep writing more, and it’s a little bit later before they hear them. If we look back historically, I think Duke Ellington composed “Soda Fountain Rag” at 13, so there’s a tradition for this idea of composing music early.

What style or tradition were you working with in these early pieces?

Well, the earliest one was devoid of this idea of style. You see, style is something that we usually force onto ourselves. When you write music straight out of your heart and not out of your head, it’s devoid of those kinds of things. So I didn’t try for these kinds of standard eight-bar phrases, I didn’t try to make a harmonic progression or anything like that. I just simply wrote what I felt like writing. That experience, from hearing it, tells me all of the possibilities other than that, because I can hear what that’s like, you see.

A lot of your work centers around this very meditational, exploratory approach to sound. Was that immediately present in your work early on?

Yes! You see, I grew up in Mississippi, and there they have a huge blues music tradition. And it’s a wide range of ideas about music, it’s not one fixed standard. For example, you would never hear John Lee Hooker playing so-called 12-bar blues or 8-bar blues. They don’t do that. They play the way they feel, and they make the change to the next portion of the music the way they feel. After I became 13, I started playing out with these different blues bands. So, I could observe a set of people that are already looking at, first of all, sound, and secondly, electronic sound, because the electric guitar developed before electronic music happened in the world. So these guys were having their sound amplified and manipulated, both by their fingers, some by glass or coke bottles, some by different kinds of tools that they would use to make them sound better, make the instruments sound different. Hearing and experiencing that already opened me up so that I don’t have to think about tradition. I don’t have to think about this whole idea about what’s happening in the future. I can express and make my research happen while being engaged in the present moment.

So did being exposed to all of these blues musicians growing up, and the ways they were using different techniques to extend their sound, make the work you were doing with the AACM feel like a natural extension of what you were hearing growing up?

Well, actually I can say it this way. Most of the AACM guys were interested in technique at that time when I came in there. The people that came in and brought different kinds of possibilities were Lester Bowie, Lester Lashley and me. These are all wind/brass players. Saxophonists were most interested in this dexterity and this ability to do all these things because they got all these keys that they got to work with. The trombone’s got one slide. The trumpet’s got three valves. And so your challenge becomes much larger, and it exposes a lot of different things. Like, if you listen to the recording Sound, by Roscoe Mitchell…

Brilliant album.

It’s a landmark album. It’s an exposure. He used the word “sound,” he didn’t say harmony, he didn’t say melody, he said “sound.” What the piece Sound was asked to explore was the sound that’s inherent within the instrument and the person. And if you listen to that record, the guy that achieves it the most is Lester Bowie. We can say that because it’s a document. We can look at it and see who played what seemed to be 90% of just pure sound, compared to the person that played less sound, which was Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre. He played mostly saxophone-type technology. Very creative! But very different. And the next person on there that achieved the greatest sound is Malachi Favors and Roscoe Mitchell, in those orders. You see, I experience music for the greater good of what it actually has in it, as opposed for it to make me feel good.

Going back to what you were talking about with the blues, I'd read that you had this kind of background in Delta Blues and things like that. Were there any notable blues musicians you interacted with in Mississippi?

Yeah, Little Milton Campbell, I played in his band for a while.

My stepfather was basically in the local area of the South, that is Tennessee, Louisiana, Arkansas and Mississippi. He was a blues master in that area, so I played with him as well. I played with a guy out of Chicago, Al Perkins was his name. He had a bronze record, so you can look him up. Plus, I knew all those people like B.B. King and Howlin' Wolf.

You knew Howlin’ Wolf?

Yeah, yeah.

He’s one of my favorite musicians ever. Do you have any stories from meeting him?

No, I’d just meet these people. My stepfather knew all of them, and they would come to my house because they knew him. But also, more specifically, my mother was the renowned pound cake maker in that area, so they would also come to eat her pound cake.

You’ve cited John Lewis and the Modern Jazz Quartet as an influence, which is interesting to me because I know they were really prominent in their time but I feel like they’ve been overlooked in hindsight.

They were overlooked because most of the critics misunderstood them. A majority of the listeners that divide themselves into different groups of importance for who they listen to, they missed them. The reason they missed them is because they thought that they were trying to imitate classical music. Absolute bullshit. What they were doing, what John Lewis is most important for, is that he was a structuralist. He was a profound structuralist. George Russell - a profound structuralist, and also a linguist because he created this lydian and chromatic concept of language. Ornette Coleman is also a linguist because he created the harmolodic language. And if you go a little further, the guys that come out of them are Wadada Leo Smith and Anthony Braxton. All of these people have created languages. So what I'm trying to say is that some people create languages, some people become structuralists. For example, if you go back to the very early time of this music - and I’m calling it creative music - Jelly Roll Morton was the first composer of this creative music. He was a structuralist. And along with him at the same time was Joseph Oliver [editor’s note: better known as King Oliver, the New Orleans jazz musician whose band gave a young Louis Armstrong and Johnny Dodds their start]. Joseph Oliver was not a structuralist. He transformed his music to become this kind of song-form thing. He created that form. And the majority of the musicians that came after those two followed those strains. John Lewis and the Modern Jazz Quartet followed the structuralist side. And if you look at the AACM, you would have to put them all on that side as well. The structuralist and language side. We added the language side after looking at George Russell and Ornette Coleman.

I love George Russell, that album Electronic Sonata for Souls Loved By Nature is one of my favorite albums.

Yeah, yeah! His music is pretty brilliant. But The Golden Striker by John Lewis… what’s it called… It’s got all those piazzas in Italian. It’s a group led by John Lewis, with a brass ensemble.

I might know what you’re talking about.

It’s absolutely fantastic. One of his pieces even introduced this early idea of open creation. I’m trying to think of the name for it, but it has three movements and three parts. He also wrote for string quartet. And the “Queen Suite,” do you know those?

I don’t think so.

Ok, I’m just telling you because I’m an expert on his music [laughs]. “The Queen Suite” is a magnificent orchestra of his music, and it doesn't sound like this guy, that guy, that composer. It sounds like John Lewis. He was a great composer, and very important. The reason, like I said, that he’s overlooked, is based around this misreading of what his music was, by audiences and critics.

I read that you studied ethnomusicology at Wesleyan in the 70s, and I know Marion Brown, who you worked with, was studying the same thing there around the same time. Did you work together at all in your studies?

No. He was there to get degrees, I went there to research various instruments. I learned to play the koto there, and I learned to play the atenteben, which is an African flute in b-flat. It has a bigger one that’s in f. I learned to play the gamelan instruments, all of them, except the rebab. But all the metal instruments I learned to play. I learned the south Indian flute.

The bansuri?

The bansuri, yeah. And I took an anthropological study with Dr. McAllester. He was a master expert in indigenous music traditions in America. I didn't play any indigenous instruments because they didn't have an ensemble for that there, but I studied with him to learn what that philosophical and ceremonial idea was behind that music. So when I went there to do it, I went there really because I've not seeked any degrees. My research is beyond degrees and it goes way beyond the honorary doctorates that people have given me, and it goes way beyond the doctorates that people receive as graduate doctors. Because research is in the curiosity and the light of the heart, and research will take you into discovery of every single thing that you're after. Anyone. And we all have that opportunity on this planet.

How did learning all of those instruments change how you thought about your own music?

Well, at the time, we were looking at this whole idea of world music, and essentially my notion of world music was very different from those people that were in world music. Most of them would go to Africa or Asia and record with some of those people. I define that as ethnic music. Or it could be music from Ghana, Nigeria, Angola, or music from Thailand, or it could be music from the Middle East. My definition of world music included all the music on the planet, and it included the science and the application of the practical technology of how you play the instrument. And that included Europe and the violin as well as the piano. Most people excluded those from world music when they were talking about it because they were talking about ethnic music, you see? So what I learned there was how to play those instruments, how to think about a global notion of music, and the global notion of music followed the same principle for me as a global notion of humanity.

What were the most important things you learned from Muhal Richard Abrams?

To follow your own dream. Unlike most people in the AACM, Lester Bowie and I never studied with Muhal.

Really?

Yeah. Everybody else that’s there that’s from Chicago, they all studied with him. Roscoe and Joseph and all of them. And there were a few people who came from the outside that didn’t. Lester Bowie, John Stubblefield, Wadada Leo Smith, we were the main guys that came there and brought stuff. When I came to the AACM, I had already written my first string quartet. I had tons of music. Muhal invited everybody when they first came to the AACM to bring music. Nobody ever took him up on it until I did it. He told me the first week I came there that I could bring music. The second week I brought music. And then the third week everybody started bringing music.

So when people ask me that question, I try to clarify it by saying that in the AACM there were two batches of people. There were Chicagoans and outsiders. Outsiders in every meaning of the term. Most of them brought stuff there, meaning that they brought things that they were already doing, and that makes them also outsiders. Understand this word outsider, it’s not this notion about how it appears in society, it’s not that negative impact, it’s a positive one, coming from somewhere else.

Absolutely. And I’m guessing you counted yourself as one of the outsiders?

Yeah, I’m an outsider. And you can't become an insider when you're an outsider, and an insider can't become an outsider. You have to work with what you have. And both zones are positive, because look what we created as a collective. That's something that absolutely just changed music forever.

What’s interesting is that you’re from Mississippi, and obviously a big part of Chicago’s history is the mass migration of people from the South into Chicago.

Yeah, three million people migrated during the Great Migration from the 50s straight across.

Yes, so even though you were an outsider, in a sense, coming to Chicago from the South is a very Chicagoan thing.

Yeah. Well, you know before I got there I had already lived in Italy and also in France.

Really?

Yeah, because I was in the military.

When were you stationed there?

I got out in… 1965, I believe. That’s when I entered Chicago, when I got out of the army.

Were you working on music while you were in the army?

Yeah! I’m telling you now, I got out in 1965, I came to Chicago, I brought my first string quartet, I had tons of pieces. I have a file, a box in my archive, that’s all state of the art music from that time.

I know the Art Ensemble of Chicago was in Paris for a period in the late 60s and early 70s.

All of us were. Braxton, Jenkins and Smith, and Steve McCall, and the Art Ensemble, which at the time was Lester Bowie, Don Moye, Roscoe Mitchell, Malachi Favors and Joseph Jarman.

Had you already made connections in France from being stationed there?

Oh, no, I did not. No.

So it must have been a totally different experience.

It was, yeah. But the beautiful thing is that we decided - the Art Ensemble and Braxton, Jenkins and Smith, the two different groups in the AACM - we decided by consultation with each other that we would take off and go to Europe. And the reason we did it is because Charles Clark, the bass player, passed away at the age of 23 from a brain hemorrhage, coming from a rehearsal downtown with the Civic Orchestra. He was part of Joseph Jarman’s quartet. Six months before, Christopher Gaddy, at age 24, he died from kidney failure. He was also part of Joseph Jarman’s ensemble. So, we saw that people were passing through transition at an early age. We made a decision to get out of Chicago and spread this music worldwide. That was our mission. We didn’t have consultation with nobody else in the AACM. The Art Ensemble made their decision, Braxton, Jenkins, Smith, we made our decision. Braxton went a month or a month and a half early, and Leroy and I went about a month later.

I think you accomplished your mission there.

Yeah, that was the goal, but we wanted to do it because we wanted to give ourselves a chance.

I know you played on Brigitte Fontaine’s Comme à la radio during that time. How did that come together?

Well, at the theatre that we played at - the Art Ensemble and Braxton, Jenkins, Smith - was called the Lucernaire, and the Lucernaire was the place to play, and be, for this creative music. In our audience, on any given performance, you would find people like Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman, Archie Shepp… anybody that was in creative music in Paris would be there. Brigitte and a few other people would come there because they also had a theatre group that also presented and performed in the Lucernaire. Joseph and I met her, and the two of us started playing with her and that theater company that she also worked with. And I might tell you that that record that she did sold over a million copies.

Oh wow, I didn’t know that.

Yeah, it was an extremely big hit. We also recorded a lot of music that was never released in that context.

I’d love to hear more of it, that’s a brilliant record. What did you learn from that experience?

Well, it actually was a confirmation that music has no borders, and secondly, that when you think about music as a commodity, it limits how you understand it.

Definitely. It’s interesting, because the album goes against that idea of music as a commodity, but at the same time it sold so many copies.

Yeah, but in spite of the commodity, because all the music is considered a commodity. Just like Campbell’s soup. And I mention Campbell’s soup because that’s what the great painter, what’s his name?

Andy Warhol.

That’s what he was trying to tell people. That’s why he did all the Marilyn Monroe paintings. He wasn’t putting Marilyn Monroe down. He was complaining against art being looked at as a commodity. And I read many people talking about his works, and… they don’t fucking get it. Artists constantly speak the truth, and the truth is just the truth.

But sometimes when you speak the truth, it actually pays off well because it speaks to people. I guess the Fontaine record would be an example of that.

Yeah, because for it to not be a commodity all you have to do is believe that it’s actually art.

On the topic of records you played on, one I really love that I was surprised to learn you were involved with was Melvin Jackson’s Funky Skull.

Yeah, Lester Bowie and I. That melody that we play on there, we wrote that. We didn’t write it out in pencil, we put it together in the studio. He took a lot of courage to invite us to play on that. He was a progressive thinker.

It’s fascinating, because he was working with these AACM musicians on a record that’s mostly based in funk. Was that something you and your contemporaries were interested in at that time?

Well, one of the responsibilities of being a performer is that when people ask you and you respect them, you have to perform with them. And that builds and it widens and expands our community, to work with him. If, say for example, that band had ever played live, it would have been magnificent. But nevertheless, it was on Limelight Records, and it expanded what we were doing in that context to a whole other different audience. So, yeah, you love to work with other people. I mean, like I say, I played in blues bands and all kinds of bands. I play across borders or across boundaries, you know, and it makes it important for me to think like that, because otherwise everything else is kind of an imprisonment.

I know you practiced Rastafarianism in the 80s and that’s where you got the name Wadada. What drew you to Rastafarianism?

Well, essentially because it was a spiritual and mystical system looking at Christianity in a very different light. You have the Christian and various religious groups that have a branch of mystical teachings that extend from it, like Sufism and Islam, for example. The Rastas natural mystics took this language from the Bible and reinvented it, made it have a modern day vision, used it as a revolutionary slingshot, to bust open the ideas of liberty and justice. Any of the music coming out of there that has this spiritual connotation to it is intended in that way. One of the things that's very peculiar about the Rasta’s tradition is that when they do their reasoning, which is a very alert, awake form of analyzing and talking about stuff, if they read a text from the Bible or from the newspaper or any other context, they don't read it as if it's in the past. They read it as if they are a part of it, at that moment, while they're reading it. Like, for example, if they're reading a text out of the Bible that says something about the guy that wrote the Psalms, whatever his name is, Solomon. They are actually in court with Solomon. They're not like “this thing here” and “this text here.” They're part of it. That's unusual. That's a psychological treatment of the material that had not been understood by any Christians or anybody else on the planet. Things like that, that's some of the fruits of what they were into as a mystical group of people. I wouldn't call them religious at all.

What would you call them?

Mystics. And Bob Marley named them, he called them natural mystics. He added to it, he said “natural mystics, soul rebels.”

I've learned an awful lot from them. I learned that you take every step in life to be serious. And what does that mean? That means that you read every situation. You do your research. You share this notion about love, real sharing of love.

Do you still practice today?

No. I reverted to Islam around March 2000, because I took the Hajj in 2000. So that’s about 25 years of practicing Islam.

So you were practicing Islam before you were Rastafarian?

No. In Islamic tradition, the whole world was born as Islamic people. There are two, there’s the tradition where people are born into Islam, that is, if their mother and father is Muslim, and then there’s this other tradition of the people of the Shahada, that is, people who take the confession of faith. And the people that take the confession of faith are considered to revert to Islam. I'm one of these people who did the Shahada, had the confession of faith. And there's a Hadith, which means a tradition or teaching of the prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him. He says they saw a dream where there was brown sheep and white sheep and et cetera, and that one group of animals outnumbered the other. And they asked the prophet, “who are these people?” And the prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him, said that those are the people who believe in me and have not seen me. They are the Shahada. They're the largest. They're larger than the people that are born in Islam.

What was making the Hajj like for you?

Well, they described it as a judgment day. You see, it's very hard, very difficult. You have people from all over the planet whose social and cultural experiences are all quite different. The size of the gathering when I went there was a million and a half people or two million people in Mecca. That means that when you are outside, you can only take a step that's so big at a time because there’s so many people. That's a difficult thing to do.

I got lost twice there. One of them was really scary because I couldn't find my way. I couldn't catch a ride. I was directed to walk on this highway, and at some point I'm facing just a desert. I didn't go into the desert because for some reason I looked back and I saw a person go down a rail. I ran back to go down that same rail, and that's what kept me from going into the desert. If I'd gone into the desert, I probably would have froze, because in the desert, night is very, very cold.

Yeah, I can imagine. Did you feel like that was a sign of something?

It was a sign. I had dreamt before I left that I would get lost.

Really?

Yeah. I couldn’t catch a bus. That was before I went on the Hajj.

The guy that I saw go down the rail, I ran after him as hard as I could and I called him and tried to ask him something and he never spoke to me, for two reasons. One is that he didn’t speak English, and I didn’t speak Arabic, and the other is unknown. But what he did do, he brought me off of that highway that would have led me into the desert and mountains, and to me, that's similar to faith or miracle, or something of magnificent emphasis. ‘Cause the next story is that, when I got down and started walking, I came into this town, it’s called Mina. And that’s the town I was looking for! And as I keep walking, I see these young men, maybe four of them, standing up on the sidewalk. They're young, they’re really actively talking, and I walk up and a guy looks at me and says “can I help you?” [laughs] I said “yes! I’m lost!” He told me what to do, where to do, etc. So, to me, that’s a moment of power. Not my power, but the power of how you be and what is happening to you. On my final Tawaf around the Kaaba, I stepped out of a door, and I never noticed any of the names of the doors before, because every day I've been in the mosque. You can't really say, “I'm gonna go here to this door.” You can't do that, because you've got millions of people there. You would get up and flow with the crowd out the door. The door I flowed out of with the crowd was the door of Ishmael.

Really?

Yes. That’s the confirmation of my name. I took the name Ishmael as my Islamic name.

I had read somewhere that you’ve changed your name with different faith experiences, but you always add your new name to your previous name, which is really interesting to me. I’m guessing it’s because you want your name to reflect all of these different experiences?

Yeah, and also I have to remember that my mother and father named me, and the naming ceremony, all over the planet, is one of the most important things.

How did you get involved with Derek Bailey and Company?

Anthony Braxton had done some performances with them, and he asked me if I would like to be involved. Derek had already asked him if I would like to be involved. So I said yes, and that made it happen.

How was that experience different from what you had done with the AACM in the US?

Well, basically, they rely upon free improvisation, and in America we're not limited to ideas of style and stuff like that. He believed in no language, that you just do, and here we don't really believe in something that's void of everything that we do. He believed that music has no message, none. Even Robert Johnson put messages in his music. So there's a lot of what we experienced as artists that they didn't experience as artists.

And if you look over now, the free improvisation movement has probably been a little bit inhibiting for people in Europe, because they've kind of used it as a brand, and whoever breaks out of the brand - if in fact they do - they're not part of the brand anymore. So people are struggling to find identity outside of that, and they find it very difficult.

It’s funny, because Derek Bailey described his playing as non-idiomatic…

But it was an idiom, you know.

It became one, definitely.

No, it was in the very beginning. When you say you have to do just this, that’s an idiom. And a play of words just doesn’t change it. If you’ve read his book, Improvisation - did you happen to read it?

I did, yes.

In that, he used all the European guys as a way of trying to establish a link between improvisation and them. And none of those guys that he interviewed were improvisers. None of them, not even the guy from Spain.

Paco Peña?

Yeah, yeah. In fact, he states quite clearly in there how he does his stuff. So there's a political and a cultural connection that's involved with the book that doesn’t make sense. It makes sense for him because he's trying to, in retrograde, prove the long connection with improvisation in Europe. And I can prove that it didn’t happen there. People point to Beethoven, they point to Bach, they point to all these guys. And I can say quite clearly that even if those guys improvised at the piano, they never made it part of their tradition. And the reason they never made it as part of their tradition: paper and print machines was the medium. No fault of theirs. For me, they are still creative artists. But the print press was the medium. For example, here, the medium starting with creative music from the earliest time was always recording. It's hard, evidential proof of what was happening then. You can't do that with Europe because their medium at that time was paper and the printed press, and things traveled much slower by a printed page. The score is printed, it's sold, the person learns it, plays it publicly, etc. A record gets there, you hear what that master did instantly, and you already got the music and it's already finished. Nobody has to learn it, nobody has to do anything. I'm talking in terms of how it communicates and gets out into the stream of the world.

Maybe somewhere down the line there'll be another medium that's very different from what we have here. And if it is, then this one here that we're looking at right now would look just like the printed press medium back then. So it takes nothing away from Bach or Beethoven or those guys. I don’t say they couldn’t improvise, maybe they did improvise. But because it was not part of their medium, it took no importance whatsoever in the culture.

Considering all of these differences between you and Bailey and these other European musicians, was it difficult to play with them?

No, no, I loved playing with them. They were great artists. I criticized their politics, and their cultural persuasion, but not their art. We made some wonderful music together.

Do you ever have any challenges playing with different musicians?

No, it’s not a challenge at all, because when you strike up the band, there’s no nations or race or gender present.

How did you get to know Henry Kaiser?

I met Henry Kaiser in the Bay Area because I used to play up there quite often. And we decided to put together a band called Yo Miles!, which we dedicated to playing some of the electric music of Miles Davis, mostly, but also some of the pieces that I wrote. I was the only guy in the band that was composing music. And so we started dialoguing and having a conversation about how to do this music and maybe set up a recording, etc. And then after that, there's four LPs of it.

My understanding is that everyone loves those electric Miles albums now, but at the time you were recording they were kind of neglected.

Well, they sold well. Bitches Brew was a gold record. It was just basically the critics and people who sent up fences around whatever they think is going to be their art that they listen to, and you have it in every generation.

Reading about how people talked about those albums at the time is crazy to me, with people calling Miles a sellout for making that music.

It wasn’t rock n’ roll, it wasn’t rhythm & blues, it was creative music. And not only that, I can mention a few pieces that eclipse almost all the music on the planet, and that’s Agharta and “Calypso Frelimo.” Not only does he eclipse all music in his own creative music, but it also eclipses all the music on the planet.

Definitely. I have trouble listening to that music sometimes because it makes everything else sound weaker in comparison.

Those two pieces are landmark pieces that will never, ever be duplicated.

For sure. I love the conceptual framework you’ve taken with your more recent releases, making projects inspired by the national parks, the great lakes, and civil rights heroes. How do you go about capturing the essence of these people and things in your music?

Well, if I do individuals, I do psychological profiles, like “Dred Scott, 1857,” for example. He was the person that opened up the first debate in this country about race, even though he was a slave and owned by a family of people. Being a slave, you’re still a human being, and he along with the abolitionists of his time took his case to court in St. Louis. He lost the case, but he became the most known African American during his time. So you do a psychological profile of him, or you choose to look at his actions, or you choose to look at the court event. What I chose to look at was him and his actions - the choices that he made. If you look at JFK, I chose a few frames from the television stream of his burial. If you take Medgar Evers, I chose the four or five seconds of when he was pulling into his garage driveway and was shot in the back, with his family standing in the doorway looking at him. I chose those four or five seconds. Each of those pieces, all three of them, are looking in different directions.

[we paused as Wadada took a phone call; one of the musicians in his group Revolutionary Fire-Love was caught up in flight delays]

Which musician was that?

Yosvany Terry, the saxophonist.

That’s rough.

Yeah, it’s lots of money for planes and cars and this and that. It’s all too difficult.

Well, I know you just released a new album with Vijay Iyer, Defiant Life, on ECM. Your first album on ECM, Divine Love, which is one of my favorites…

Yeah, it’s a classic.

Absolutely. That one came out 45 years ago. How did you first get involved with Manfred Eicher and how have you kept that working relationship over so many decades?

Well, I met Manfred in the sixties, and I’ve known him as a performer. He’s a bass player, and we’ve played together and stuff like that. We became friends in the sixties and we remain close friends today. He’s a magnificent producer and audio master, and he just doesn’t do it as a way of making a project. He has ideas about the project, which he explores and develops. He’s a person that anybody on earth should probably dream to work with if they have not had the opportunity.

What’s something you haven’t done musically that you want to try?

…. Well, I don’t really think in that way. What I think about is, how do I find the next project that’s going to be uplifting for me and everybody else? My basic concern as an artist is humanity, and being able to address and connect with humanity throughout. That’s my main concern. I don’t really care if a product sells half a CD or half a record, that is broken in half and so on. I don't care if it sells unimaginable numbers. None of those things bother me, because I will live, even if it's not experienced by anyone.

Best interview I've read in a while.