An Interview with Van Dyke Parks

Some people have seen it all, and then there’s Van Dyke Parks. Parks is most well known for his work as Brian Wilson’s lyrical partner on the doomed Smile sessions, and for his work with the Beach Boys in the years after. As a producer, arranger, and session musician, he’s worked with The Byrds, Randy Newman, Ry Cooder, Harry Nilsson, Little Feat, Ringo Starr, Haruomi Hosono, Fiona Apple, Joanna Newsom, and too much more to mention here. His music has soundtracked films such as Popeye, Follow That Bird, and The Two Jakes. But in considering his musical oeuvre, the first thing I’ll always think of is his solo work, a grand menagerie of offbeat Americana and heady experimentation. Fellow polymath (and former Unknown Rhythms interview victim) Jim O’Rourke once said that Parks’ debut album Song Cycle was like every idea he could have imagined already done on one album, and that about covers it. But Song Cycle is really just the beginning of a lifelong musical journey that has ventured into many unexpected places. Over the course of two interviews - one over FaceTime and one over email - Parks and I left no stone unturned, talking about everything from his close friendship with Phil Ochs and his experience recording the Mighty Sparrow in the eye of the hurricane to his support for Palestine and learning to forgive Mike Love.

[portions of this interview have been edited for clarity]

Thank you for taking the time to talk to me, I greatly appreciate it.

How are you doing this morning?

I’m doing alright!

You’re in Chicago?

I am! Do you have any history with Chicago?

I played the Palmer House there in 1962.

What was that?

A hotel there.

Who were you performing with?

My brother’s group, the Greenwood County Singers. Maybe they were the headline, I’m not sure. We did some dates headlining and the others as openers, I should imagine that we were headlining there. It was a lovely hotel. And also I played a venue there, I forget what it was, but they had a festival down by the river. I’m not sure [laughs], it’s been so long. A decade, anyway.

Well again, thank you for giving me your time. I know you said you’ve been busy recently, what have you been working on?

What have I been working on? I did my last commission arrangement, which was a very big deal because I’ve done a lot of arrangements over the last… four decades, I guess five decades. Now, I did my first arrangement in ‘63 for “The Bear Necessities,” for a picture called The Jungle Book put out by Disney.

Yeah, that was your first big break if I’m not mistaken, right?

It was what, honey?

Your first break, like, your first job as an arranger.

As an arranger, yes sir.

So you’re retiring from arranging?

For someone else. I will arrange, but I’ll arrange for me - that is, I will arrange what it is that I wish to arrange for my own purposes. But as an arranger for other people, I am in a beta position and usually am providing a proscenium, as it were, for songs that have what they call basic tracks. Sometimes those basic tracks are very basic, and sometimes they’re highly elaborate with indications about what an arrangement would be doing to amplify, or as they say in my racket, enunciate what’s there.

I know you’ve said that hearing Spike Jonze at a young age made you realize like what could be accomplished through using the studio for musical purposes. That reminded me of something I’d read about how George Martin had honed a lot of his craft with tape editing and things like that through working on comedy records, because that gave him more freedom to experiment.

That’s very interesting.

And I know you’ve also said you were influenced by people like Yma Sumac and Esquivel, which is music I feel like people haven’t taken too seriously until relatively recently. Did you hear something in that music that other people didn’t at the time?

Well, with Spike Jonze, at first I thought that there was some kind of artifice, that it could not have been performed. Spike Jonze, as a matter of fact, all of his music, if you listen to “Cocktails for Two,” you hear the comedy, the shtick, yes, but behind that is the vertebrate of, in musical terms, of a great deal of tuneful percussion, that is things with pitch. And you Americans at one time were used to that, where great musical events in a small town would be a parade, and in the parade would be things like glockenspiels and xylophones.In Spike Jonze’s piece, there was the amplification of some instruments and things that are hit, percussive instruments, like marimbas and so forth. In fact, all of Spike Jonze’s recordings were performed. It was very interesting to me, finally, to see Spike Jonze’s arrangements amplified. I was just amazed at how, actually, all that music was performable. But when I heard the radio and that piece, “Cocktails for Two,” that I mentioned, I heard that in 1948, I would have been five years old, and it made a very big impression on me. And I realized that there was a difference between recorded music and live music. I was astounded by that and continued to wrap my ears around anything that suggested the phenomena that are available in recorded music. And that went into the next decade, which was the Eisenhower era. I’ve endured 12 presidents, Levi. So in the Eisenhower era, we had things like the phenomenon of Les Paul. Les Paul made a huge impression on me with “How High the Moon” and other tunes that he’d done with Mary Ford. Incredible, because Spike Jonze then used electronica the way no performer could possibly duplicate without having some gizmos [laughs] to employ, and his gizmos included multi-track recording. So that started coming into great play just when I emerged as an adult from music study in school. In 1963 was my first arrangement in a piece called “Come to the Sunshine” - it was for MGM Records, that was my first contract. At that time, we would record three tracks in a studio, and those three tracks were usually mixed immediately, and the music was recorded usually in one take. You’d walk into a room and the room would sound, as it were, and you’d use that in italics. Because it was that important that a music sound, that the arrangement be playable and sound good on first listening. And then we learned that microphones could be moved, so that by the time I started really employing my arrangements, I could have a mandolin in a room dominated by a couple of trumpets.

It’s very interesting. And that was impossible before microphones brought the intimacies of smaller instruments into a prominent place in the final mix. So yeah, it’s been a very interesting evolution, and I’m really grateful that I’ve spanned this evolution, the technological evolution in the studio that allowed me to be an arranger, make a great deal of success, and learn from a lot of failures in my arrangements. So I’m fascinated that you’re interested in that particular aspect of my life, because it dominated my life. My life was not dominated, although it’s been dominated by the reputation I got from working with famous people like Brian Wilson and U2 and so forth. I could go down the alphabetical list, but there are hundreds of people that I’ve arranged for that are well-known or have been well-known. So… ain’t it grand? [laughs]

You mentioned the record you made with MGM, you got that record deal from Tom Wilson, right?

Lovely Tom. Wonderful man. Many people “discovered” Bob Dylan, he discovered Bob Dylan. And he discovered Frank Zappa. I might have met him when I spent a couple of months with Frank Zappa. I stayed with [The Mothers of Invention] until an album cover. I wasn’t interested in the costume party. I was more interested in the studio than just performing live, that didn’t interest me.

The fact that Wilson worked with Zappa and the Velvet Underground but also discovered Dylan… thinking about those connections, to me, is a reminder of how radical Dylan was.

Well, [Tom] was a radical. Harvard graduate. I don’t know what his height was, but it was approximately 6 ½ feet. He was a very imposing physical figure. And, by the way, he wasn’t interested in any of that, he wasn’t interested in pop music. I don’t think he was really interested in Zappa, for all of his eccentricity… and talent, he was a talented man, for sure. I admired his talent - I didn’t approve of all his decisions, social and otherwise. But Tom Wilson was interested in music, and as a matter of fact, I think, was a fine jazz aficionado. So it was a surprise to me that he was interested in me, and in fact, I think it’s because he was interested in the social importance, the counter revolution, as it were, because there was one that endured for five or six years. They call it the ‘60s. And that had to do with music that had an attitude, which was truly revolutionary. I was grateful to have his attention at all.

Although it was as an artist, and I knew quite frankly that my importance probably lay in my ability to be a beta male, to be able to aid and abet musicians who wanted to have a signature power and be alpha in this new social order. And I had a great time doing it. I had a great time being in a beta position, that is, being able to arrange and get out of a studio what had never been achieved before. In many cases that I did, I was necessary once present [laughs]. Truly. And to tell you the truth, Levi, a lot of that had to do with the fact that I simply had a musical literary education. I mean, I was taught music, I studied music, I read music. I was the first clarinetist when my feet didn’t hit the floor, because I was good and I worked hard. And it was through hard work that I got any prominence in Los Angeles at all. It’s not that I’m a genius and a great musician. I’m surrounded by people of greater talent. And I think that that’s been my gift. I’ve been lucky that way.

I get the sense that you were really different from all of these people you were interacting with in L.A. during that time - obviously you had all these ornate literary and historical interests. Was that something that made you unique in that world?

Well, I think what made me rare - not unique, but rare - is that nobody wanted to play piano. You had to be gay if you were playing piano, or privileged or something. Everyone wanted to play guitar like Bob Dylan. We all remember - I’m especially aware - that 1963 was a hallmark year, because that was the year that the Rolling Stones made their first records. The Kinks, Manfred Mann, the Beach Boys, Bob Dylan. In fact, that was the turning point for music. And I think that that’s really when the ‘60s began, when America awakened out of this Eisenhower-era narcolepsy, the sleepwalk of the benevolent victor of World War II. That was a good day for Norman Rockwell. There was nothing wrong with the American dream, and the one that we unfortunately haven’t awakened from.

But that was a very important year to the recording of music, 1963. And that’s just exactly when I found myself necessary at a studio, because a lot of the people who embraced the cultural revolution just didn’t sit down and play the piano [laughs]. They were out there out front wanting to get laid and play the guitar. Or versa vice, play the guitar and then get laid. But neither of those things were principal in my mind. I had played guitar, and I played very well. I played a nylon string guitar, and I did so because I love the music of South America, basically. People like Luiz Bonfá.

Oh yeah, he’s brilliant.

I really recommend him to you. It’s the attitude. Today it was announced in the New York Times - which I read for the crossword puzzle, of course - that the United States, it was said by Trump, wants to lead the Americas. It seems America wants to govern the Americas - past the “Gulf of America.” This to me is a very sad indictment of our hegemony, and the rock revolution, and the insistence that pop culture should be the only culture, and the only way to to express humanity. And I think humanity finds great horror and grief over the, you might say, the British blues bands. The acquisition of American folk music and music of the laboring class to such a well- heeled hegemony of American lingo run amok as if it were the only language we should speak. So I think that ‘63 was a place where I had a departure from the music I love, that is, the music of the Americas. I came to California and I heard a lot of Pan-American music because we’re a nexus to what’s south of the border. And that’s when I met Astrud Gilberto on her first night of performing in the United States, at Howard Rumsey’s Lighthouse Cafe. You can look it up if you want to. I don’t have to, I was there.

[laughs] I’m a huge fan of that era of West Coast jazz so I’m aware of it.

I was there the night that she played that club, and went back to meet her in the kitchen. Behind a curtain there was her dressing room, and I almost met her. But I was 20 and I believe she was 23, and she was sobbing, I think, because she was in shock from having just performed her first show in the United States. And also, she didn’t speak English and I did not speak Portuguese. So there we were. And I decided I was over my head and I never did meet Astrud Gilberto. But I loved Bossa Nova and Samba, which my son, who’s now 42, and I play together in our spare time.

That’s amazing.

So I believe what has drawn you to me is that I was a marginal character in the music business, in the pop revolution, etc. You mentioned the Beach Boys. In fact, I had very little interest in the pop culture, although I was heavily complicit in it [laughs]. And this is true. I’d been so busy, I didn’t have time to study what we were doing to the world. I was simply trying to learn what was possible in the studio. And that continued until this month when, as I said, I just did my last commissioned work as an arranger. That was a big, big deal for me.

Yeah, congratulations.

Thank you.

So, was there a moment when you first got a sense that there was a much broader world of music outside of American pop culture?

Well, I went to a boy choir school. I studied and performed music all over the place. We used to go up to New York City and rob St. Thomas of their jobs. We were the best boy choir in America. And that was located in Princeton, New Jersey. So my musical appetite and my musical library was outside the purview of American pop culture, well beyond just the lingo of Les Paul and Mary Ford and Frank Zappa and the Stones and the rest of it. I had already had a tremendous opportunity in music as a child. I studied clarinet, and I studied not only the music of the church, but American popular music, which was of the big band era. My father had a dance band to get through medical school during the Depression, so his instruments went to his four sons. I was the youngest of four boys and I got the clarinet. The double barrel sousaphone, the French horn and saxophones and the cornet and so forth, all the brass instruments went to my older brothers. I had the clarinet. That was a big benefit on a night of Christmas caroling, because I had a reed instrument and they all had brass instruments. And if you’ve ever played a brass instrument in freezing weather…

Oh no.

[laughs] … you’ll know that the clarinet was a godsend. And so my musical education was absolutely encyclopedic as a child. I loved all kinds of music and I still do, except that which has hostile origins. I think music should be used as an instrument for humanity and to bring people together.

Was there a point when you realized you didn’t have an ordinary childhood?

Well, I knew I didn’t have an ordinary childhood with parents as musically adroit as mine. My mother and father could waltz, but they could jitterbug, and they did. And they were Christian in their religion, but my mother could speak Hebrew because she studied it. So, yeah, I knew that I had a special place in life because I had special parents who were liberal, asking questions, maybe leaving more questions than providing answers for me. I would find my answers in music, and I knew that early in life because nothing else interested me like music. I knew that right away. I didn’t study when I went to Carnegie Tech [laughs], which is one of the great engineering schools of the United States. All my classmates got great advanced degrees in engineering and so forth. Now they own wineries in places like Chile and Peru and so forth, because they were engineers. I was the only student in my fraternity that was in the arts. But yeah, Carnegie Tech had an arts department. So when I was 18 in college, I had no promise of a job - except if I stayed in school for an advanced degree, I might be able to be a piano teacher somewhere in a junior college in Pennsylvania. That didn’t excite me. What excited me at that time was the beat poets of California and the authors, Steinbeck, Ferlinghetti, Lewis McAdams and so forth. Not Ginsburg, I thought that he had a lousy attitude, but positive poets who expressed what was the California dream and what that was about to be pronounced in the California Hotel. And California was the place I wanted to go. It represented a frontier of thought. So I stopped studying music in October of 1962, and I accepted my brother’s invitation to come out and play in California and play in the coffeehouses of California. And we ended up playing work songs [laughs], because I was from Pittsburgh and we called ourselves the Steel Town Two. And it was a travesty, of course! But there’s one sure thing. We knew work songs and we were broke. We used to go behind the supermarket to glean yesterday’s vegetables, along with the poorest people of Seal Beach. I knew what it was like to struggle economically, and I knew that my sentiments were with those without. I was born with parents who taught me the value of defending those who had less than I, and the working class from which we all have sprung. And I found all of that changed my musical diet, and all of a sudden I wasn’t involved with important music that didn’t matter. I was involved with unimportant music that really did matter. And that’s when the Beach Boys hit the fan. That’s when the Beatles hit the fan. Come on! I was there at the Big Bang, it was my good fortune that I was, I feel, because I ended up arranging for people who came from that age of protest, as it were. I was horrified by the problems we had, napalming Vietnamese children and so forth. So I produced Phil Ochs’ last album, a protest singer who died, a saint in my view. And I served people that I felt did matter, and that’s where I got my reputation.

I watched a documentary about Phil Ochs a few years ago and I remember being surprised to see you in it, but when I realized you had worked on Tape From California it made more sense to me. How did you end up meeting him?

I loved Phil and I’ll tell you the truth. I was very close to Phil at the end, and he was just so insane. This problem with Allende, and the United States trying to push South America around. They’re still doing it, now with that spoiled brat that’s there in the Oval Office now. It’s just shameful that Phil Ochs did not live to tell the tale anymore. It grieves me terribly that he isn’t with us today.

I definitely think he would be a helpful presence in these times.

What a sharp blade. We need sharp blades! [laughs]

Absolutely. People always talk about Phil’s politics and his lyrics, but less about his music. I was wondering, what was he like as a musician? What were his musical instincts?

Oh, I’ll tell ya. To me… bel canto is what they say in music. He had a great voice, and he had a great, natural relationship with the guitar. As a rhythm guitarist with a voice, he spoke volumes. His interest in bringing me into his world was that he assumed that I was some kind of high class cat who would get him an orchestra, and it would elevate him. In fact, I thought that it was the wrong decision for him. I really did. I was quite close to him. They lived adjacent to Laurel Canyon where I had a house. I had met Phil in ‘64 in Greenwich Village and spent part of an evening with him and Bob Dylan in a room when Phil Ochs decried this business of amplified folk music, and I agreed with Phil. And of course [laughs], I was so definitely wrong. Bob Dylan proved that in his argument. He left disgruntled because sometimes people say Bob Dylan wanted to be Phil Ochs. I believe that, certainly. But he wanted to be Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, too. He wanted to be a lot of people, but, in fact, he became himself. And a lot of people thought they could thrive simply because they couldn’t sing as good as Bob Dylan. But yeah, I think he was misguided to make his last great oeuvre in the studio an orchestral event. And that’s why I was involved with Andy Wickham, his roommate, who was my closest friend. Andy was the head of Country at Warners when I was the head of audio visual services.

On Song Cycle you were working with all these influences from early American music. I think you described it as sort of an investigation of Americana, this American identity, in the context of the turbulence of the ‘60s. Did you ever have any fear that people would hear that and potentially mistake it for an unconditional celebration of everything about America?

Well, I hoped that the record would appeal to my parents. I discussed their war letters in a piece called “The Attic” on Song Cycle. As a matter of fact, Song Cycle was written as I was recovering from my brother’s death. My brother was the youngest person in the history of the State Department of Foreign Service, and he was a vice consul to Frankfurt. In 1963 he died, and that was on my mind. I was still reeling from it when I did my first album. There was no way to ask a person to write some toe tappers that were going to please the pop music crowd in those circumstances. There were no toe tappers on Song Cycle. It sounds like somebody was trying to learn how to use a studio, and as a matter of fact, that’s exactly what it was. I was lamenting my brother’s death and trying to learn how to make a living. A lot of people at that time, my good friend Steve Stills and many others, they would get advances from a record company so that they would either buy a lot of cocaine or a nice house in the hills. I spent my advance on an orchestra because I wanted to learn how to address orchestras in this age of studio recording and still keep a mindful obligation to the technological development that studios gave us. I got seven balalaika players - they would not have been heard in an orchestral environment unless we’d been able to move microphones around. So on Song Cycle I was learning. I didn’t even think anybody would listen to the record. It didn’t occur to me that anyone would listen to my record. There was no conduit. The public could have been all ears, but there was no way for anyone to hear my record. FM college radio stations were emerging, but it was a growing market. Radio was just learning how to accommodate people who could write toe tappers that still had a cultural revolution in mind. Honest to God, that’s true. And so I was certainly unqualified to find any way to give Warner Brothers their immediate gratification.

Everyone wants it now. Instant gratification has become the hue and the cry. In those days, within one fiscal year, Warner Bros wanted me to reach black ink. Well, they didn’t get it. It took them a few years. They complained bitterly that they didn’t know what to do with me or my record, but in fact, I’m sorry, what has it been? 60 years later, Warner Brothers is still raking in the dough, claiming that it cost them to accommodate my eccentricities. They learned a lot from my eccentricities. I heard it was quoted, the leader of R.E.M. just said, they wouldn’t have gone anywhere else but Warner Brothers because I was there. So I know that I was an advantage to Warner Brothers, not only with producing Randy Newman’s first record and Ry Cooder’s first record and other artists’ records of that sort. Not only that, but I brought them the first audiovisual department, the first promotion films preceding MTV. My only difference was the contracts that I asked artists to sign gave them 20% of the net proceeds. It gave artists an income stream so that they wouldn’t have to die on the road like Janis and Jimi Hendrix and Lowell George and others that I have known and loved, who were pushed into the narcotic ramming speed of live performance because the record companies screwed them so royally. I went into the record company, got into a position of being able to review their contracts where they pay artists on 90% of monies received. Warner Brothers was turning from a million dollars a year to a billion during the time I was there. And in all that time, they gave the artists royalties, and small royalties, based on 90% of those net profits. “Why 90%?” I asked the head of the company. He said “breakage, my boy.” I said to him, “Mo, records are made of vinyl. Nothing is breaking. We’re not using carborundum. Why is it 90%?” He wanted to know why I was offering artists 20% of the royalties from the rental of these promotional videos I was doing. I was not long for the managerial ranks of Warner Brothers Records. They would rather talk about the eccentricities of Van Dyke Parks and the fact that he didn’t have a “gen-re,” as they put it. [laughs] Is this being any help?

No, this is great! I mean, thank you for telling me all of this, it’s fascinating.

It is, isn’t it.

But if I’m not mistaken, you made Song Cycle right after you had drifted away from Smile, which was also a very ambitious album that the record company people were not thrilled with.

Of course. By the way, my sympathy goes with Mike Love. There’s no reason to think that he was wrong for objecting. He didn’t know that a guitar could play that cello part on “Good Vibrations” that I asked Brian Wilson to include, the rapid eighth note triplets, which I think became the ruby slippers of the song. I think that that is really what secured my continuing with the Beach Boys. But Song Cycle naturally was an inconvenience to a lot of people. It wasn’t getting laid in the backseat of a Chevy. Or a Ford! It wasn’t a teenage love lament. No, it was, I think, a studious regard for the potential of the studio to change what music could become. And it continued to my last studio album with Warner Brothers, which was called Orange Crate Art.

And in that, you’ll notice I invited Brian Wilson back, because I felt I owed him everything. I didn’t owe him my life, but I owed him a tribute, because he came to me when I was vaulting pay toilets, when I needed a job. And he gave me one. He gave me $5,000, which bought me a Volvo so I could get off the motorcycle when I came to his house to write lyrics. I owed it to Brian Wilson to make my last record, a tribute to him as well. And so when he was at the nadir of his recording career, and I knew that I was exiting my recording career - I wasn’t exiting actually, but certainly exiting Warner Brothers - he and I did that together. And in the reissue, they have an additional LP, without the beautiful cover of Brian Wilson’s great vocals. I got five vocal tracks out of them on every song. It was the fact that you can hear the instruments without the vocal, and you can hear the emergence of a production where live instruments are included with the prelay of MIDI information. So, we have tremendous technology in its infancy being combined with analog studio performing. And it’s clumsy. You can hear my mistakes. I love it because I was scared to death that it would come out when Omnivore Records asked me if they could do it without Brian’s voice. Of course, I was frightened to death, because it would reveal how clumsy my work was in bringing electronica, the prelay of MIDI information, together with the real goods, the rosin of the bowing arm, which means a lot. And you can hear my efforts to bring it. That’s the last time I think you’ll hear a bass harmonica solo, at the end of “My Janine.” Because Tommy Morgan, who is the harmonica player, he’s dead now and no one else plays that instrument. We’re losing a lot of American instruments out of all these wunderkinds with their electronica at home, who have no idea what a bass trombone does, or why it’s differentiated in the embouchure of someone who plays a French horn. They could care less. American instruments and folklore are at peril because of advances in electronic music and its dominance, its ubiquity at the cost of losing things like bass harmonicas. You just can’t find one. There is no one who plays with the alacrity, the speed, the cheerful results of a genius like Tommy Morgan, who played every damn harmonica solo on a Beach Boys record. Now, what did it do when you heard a Beach Boys record with Mike Love on them? What you heard was a record where the composer decided that a harmonica belongs in the reed section with the saxes. And guess what? It’s a reed instrument! Well, la-dee-da. Brian Wilson had that impact on saving and savoring American folklore, and he brought it back into our faces. And when Brian died, I’ve got to tell you, sir, when Brian died, everybody gave me a call - except you [laughs]. They wanted to know how I felt about Brian Wilson dying. In fact, when Brian Wilson died, he took an era of American culture with him. It’s gone. That era that I shared with him. Barbershops, Four Freshmen, five trombones, careful vocal arranging. You’re not going to hear it in Maroon 5. It could be Maroon 10. It’s still marooned.

[laughs] Well said!

Well said. You’re marooned, baby, because you’re a mile wide and an inch deep. Actually, I’ll tell you the truth - with no insult to Maroon 5, who perform music for people who I guess are lonely in elevators. But we must be grateful to all of these musicians, no matter what they do. And I don’t have any arrogant disclaimer to anyone who’s a musician. I’m glad they’re not into munitions. I’m just glad they’re not shooting at me. Because music is… this is the language we need to employ to get out of this dilemma that we’re in. So what questions do you have about arranging [laughs] or anything else that I’ve done right or wrong?

I mean, I wanted to talk about Discover America a little bit, because I love that album.

I do, too. I think it’s a great album.

And I love it, in part, because I feel like you might be the only white guy who’s ever made a Calypso album that wasn’t completely embarrassing.

But I love them all! You’ve heard Robert Mitchum before?

Oh, of course, yeah.

Maya Angelou, have you heard her Calypso album?

No, but I’m aware it exists.

Oh, believe me - can you see my face? Can you see my face?

[laughs] Yes, I can see your face very clearly.

She is top notch. In fact, many people have loved Calypso. My parents loved “Rum and Coca-Cola.” Talking about music and monetization, by the way - it’s always been interesting to me how these musicians have gotten whittled down to nothing in record contracts - it seems to me that “Rum and Coca-Cola” was the test case. There’s a book called My Life in Court by Louis Nizer, who was a great advocate for human rights.

Does that go into Lord Invader and the whole copyright case?

You got it. It has to do with the British Performing Right Society. I wanted to find music that could express a view of America that came from an uninterested, uninvolved observer. And that’s what Discover America did for me. It showed me what they were thinking about us. It got me beyond “Rum and Coca-Cola,” one of my mom and dad’s sweetheart songs. So it was a place for me to go, to learn more about Calypso. “Why Calypso?” you ask, about Discover America. I did it because the words were in English, so people could understand what was being said. And the rhythms were real. It wasn’t something that a drummer from a bar blues band like the Rolling Stones came up with. No, it wasn’t some off-the-cuff rhythm made up by some well- heeled drummer in Los Angeles. They were real rhythms. So I was there at another age, and I decided I wanted to capture that. But anyway, I love Discover America, like you. I love it because I’m not being creative, I’m being reactive. I’m reflecting on something that is ours to enjoy, and I was very happy with the record. And as a matter of fact, that record, like others after it, you can still hear the influence of that obsession I have about equal rights. Coming from Mississippi, you see, that is my birthplace, where imprint occurs. When you pop out of the egg and the first thing that moves, you follow. To me, it was equal rights between the Blacks and the whites of America. I wanted to study that.

One of my favorite albums that you’ve been involved with is the Hot and Sweet album by Mighty Sparrow, which I believe you produced.

Oh, listen here! Listen here! Andy Wickham, my co-producer, he died last year. I grieve every day for Andy. He was interested in Sparrow, I wanted to do [Lord] Kitchener. And I’m very sorry that I didn’t get a chance to do that before he died. But Sparrow, I loved Sparrow. We got to do Hot and Sweet, we got down there, we were wondering “should we go to Trinidad?” No, we went down to Miami, where my mother’s uncle founded the university in 1924. His name was Bowman Foster Ashe. I loved my uncle. I find Miami uninhabitable, I can’t do it. But I could go to Miami to make a record with Mighty Sparrow - with whom I spoke last week, by the way. He’s in Brooklyn, watching reruns of Gunsmoke. A genius. Listen here - he did a show last year, 10 months ago, at Carnegie Hall. It was completely well-attended. I don’t know if there’s an empty seat, I can’t say that. But massively well-attended. Well, in a wheelchair, he did a concert. I’ve spoken with people who were there and who played with him. In fact, he can remember every goddamn lyric to every song he wrote.

Woah! There’s a lot of words in those songs too!

So, I’m saying - genius? That’s genius. When they say Brian Wilson is a genius or somebody says I’m a genius, I gotta tell them - no, I’m sorry. I’ve met geniuses. I met Albert Einstein when I was 12.

Yeah, I read about that.

The fact is, I’ve met geniuses. Sparrow is a genius. And Harry Nilsson was a genius, by the way. The thing is, we went to Criterion Studios, owned by one Mac Everman. Criterion Studios, where all that Miami stuff happened. Gloria [Estefan] - many, many fine artists. David Crosby and my friends over there, they recorded there. All doors were open for Van Dyke Parks. I still had a reputation. And we went down there, and in one day, we tracked the entire album. One day! I did that with Joanna Newsom, and Lowell George.

Oh, really?

Yes, I had two other records I’ve done in one day. And we did it in one day, and in the eye of a hurricane. Okay? The eye of the hurricane, it came directly over the studio. So at one hour, I was at the door with Jan, David Crosby’s widow. I can give her your number if you want to corroborate this.

[Laughs] I take your word for it.

History’s going to bear me out - on a gurney! But it’s true. I stood there with Jan, because she was the studio manager at Criterion Studio. I saw her at a birthday party attended by Ringo, Schmingo, Manny, Moe, and Jack, a whole bunch of people. I was the only person who wasn’t of any renown. And she was sitting next to me, so we were introduced. We stood at the door, and what rain was being whipped dead right. Horizontal rain. Horizontal rain for almost a half an hour. And we closed the door, of course. About an hour later, we came to the door, and then it was still. And then we came to the door, and this time, the rain was flying horizontally to the left. It was really amazing. We recorded that album in a day, under a hurricane, on our own self- generated power. Jerry Wexler got those generators for me. I don’t know if you know that name.

I do!

Huge, huge. Due to their humanity, we got it tracked in a day. The next day, we got the vocals done, even with a quart of blackberry brandy, and we got it done.

That’s amazing.

And it is, I think it’s the finest… reproduction of a Calypso album that has been done from that big band era.

I would agree!

And I’m very honored to have my name on it. You see, I love the big band sensibility of Calypso. The winds, the saxes, they do battle with the brass. So you hear this antiphony. You hear this dialogue between the brass and winds. It’s got this sophistication, these great rhythms.

I want to say this, if you please, sir. I should go on and get some stuff done. But I want to welcome you, if you want to come back and have another chance to answer some questions, I’d be happy to help. I want to be nice to you because of your grace and courtesy [laughs] paying any interest to a man who just retired the field!

Oh, of course! You’ve been very generous with your time.

We can serve some common good. And I also want to have a chance to worm my way into your rap. I’ll ask you about what makes you tick and how you could spare the luxury of this interview because I think it’s something we could do to make something of use to someone else.

Yeah, well, I’m happy to answer whatever questions you have. I always wish that the musicians I interview would ask me some questions!

Hey, do me a favor. Give me a heads up in, say, about a week, because I will have cleaned up a few things that require time sensitivity. And maybe you could nail me on some more embarrassing questions for Pete’s sake!

[laughs] I don’t have too many embarrassing questions. I mean, I didn’t want to talk too much about the Beach Boys because I feel like you’ve been asked enough questions about that.

We can do that, too. I’ve had it up to here, but I made a career out of talking about my close, personal relationship with Brian Wilson.

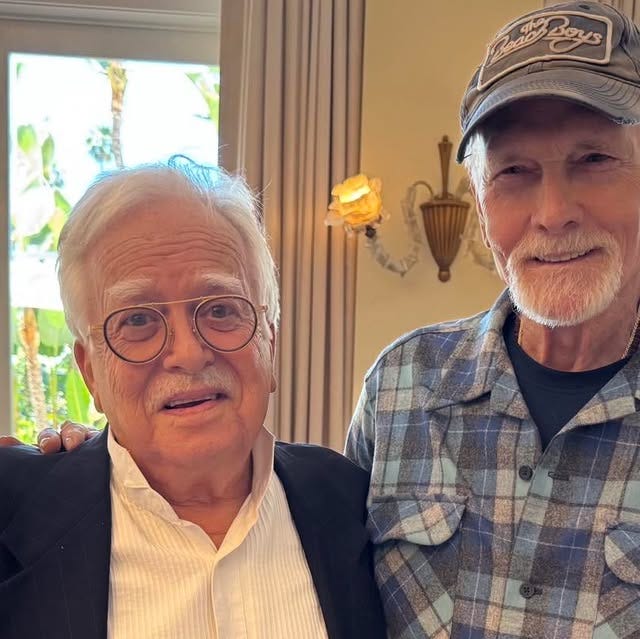

I mean, one thing I was curious about is that I saw that you took a picture with Mike Love at his funeral.

I saw him standing alone at a memorial luncheon. No one was talking with him. He wasn’t talking with anyone. He was standing alone. And everyone held a drinky-winky. They had some kind of special booze, I forget what it was. And I thought, this is ridiculous. Here’s a man, we’ve had a lifelong professional argument. I had to go up and pay him my respect. And there was nothing he could do but accept my hand when I offered it. And I thought that was probably the nicest thing that I had ever done, for me, and, I hoped, for him. The fact is, at least given the A-bomb and other considerations, forgiveness is power.

One of the musicians you worked with early on was Tim Buckley, on his very first album. What were your thoughts on him?

So many years have passed since I met Tim Buckley. He came to my flat upstairs and back at 7222 1/2 Melrose Ave. I was close enough to the targets of acoustic guitar music like the Ash Grove on Melrose or Doug Weston‘s Troubadour which became famous later, beyond that vortex between folk music, pop folk, and no folk pop. Tim had spark and was brave enough to sign a record contract deal. He wanted my help and he deserved it. Fluent in his approach to a fret board, a self-contained rhythm machine, the power of personality and strikingly cheerful in his alacrity. My only regret is that I wasn’t close enough to be able to influence him from his cause of death.

I know that you gave your brother’s song “Somethin’ Stupid” to Frank Sinatra. What was he like? Did you realize when you gave it to him that he was going to record it as a duet with his daughter?

I was at Warner Brothers myself, under employment as a studio musician, as close as anyone could be to Lenny Waronker, the heir apparent of all A&R affairs there at WB. I’ve been given an office not only to be the eyes and ears of the counterculture, but was focused on promotional documentary films with which I became the head of a department I was really interested in. My brother had written a song called “Somethin’ Stupid.” I love to say it was actually something very smart. Of course, I suspected that Sinatra might be able to sing it with his daughter, as my brother had with his intended to-be wife. I was directly under, as they say on the corporate ladder, Mo Ostin. Mo took me over to the picture lot. Warner Brothers Pictures used to be big, but it turned out it was going to go from millions to billions in the short time I was there. Sinatra had threatened to quit a label called Reprise that he owned. Mo wanted me to help encourage him to continue, so I went over with Mo to the Sinatra building on the lot. Sinatra was in a funk. He didn’t feel he was relevant after the emergence of the Beatles. He thought it was time to fold his tent. I told him, and I quote, “you can’t quit Mr. Sinatra, you’ve spanned presidencies.” Beautiful face, striking, deep, green eyes - they said blue eyes - they were beautiful and penetrating, and as we left the office here with his feet still on the desk in front of him, he looked in our direction and said “thanks, kid.” I learned a lot. Years later, I was in Musso Frank, a swank old restaurant, the oldest woman in Hollywood. I was with Rufus Wainwright who had just recorded my song “Black Gold”. I saw Nancy Sinatra at an adjacent table talking to a man about big deals. I told Rufus that my brother had written something real smart. I told him I knew Nancy Sinatra, although I wasn’t sure I ever met her. He said “oh yeah, let’s go over and you can introduce me to her.” When we went over to her table, she rose and embraced me. Soon she recounted the story about how Mo Ostin had bet Frank Sinatra one dollar that the song would tank. Sinatra had bet that it would go to the top of the charts, which it did, evidently repeatedly. I loved my brother. He became a man of great property.

You obviously had a pretty arduous journey working with the Beach Boys, but there’s also multiple moments where you basically pulled them from the brink of extinction. What was it that kept you loyal to them even after all of those insane experiences?

I think that it’s important to remember that I was employed by the grace of Brian Wilson‘s conviction that I could do something to help him reinvent himself in his work. I did my best, and knowing that sustains me in my late age. But the reason that I am here, it’s all within the compass of the golden rule. I believe mankind was invented for the purpose to demonstrate reciprocity, empathy and goodwill. I always felt that Brian Wilson deserved the best that I could bring him, whether he knew it or not. The lyrics were also highly abstract, only as a result of music that was highly segmented, anecdotal, and of a higher spiritual plane. I felt as bewildered as anyone could be about the abstract nature of the music, but I found it to be quite beautiful and it turns out freestanding creativity, not dependent on the lyrics at all. The Grammy that I understand was awarded to Brian Wilson for SMILE was given to them for the piece “Fire.” There’s not a damn word in the music. So I make no boast about my contribution to what I think is important on the issue of “fidelity”. I went back to Brian when I felt he needed me and that it was the right thing to do.

I know your experience with working with Happy End was sort of happenstance. Were they seeking you out because they were interested in your specific work, or did they just know you were active in the music business?

I think the Japanese suffer no language barrier. They read the fine print in a world once dominated by album LPs. I was recognized for my contributions to others. I think Haruomi Hosono sensed my obsession with the values of mutual empowerment. We lived that potential in a win-win relationship that has survived for 50 years and change.

Considering that you worked as a child actor, have worked on a number of film scores and that your music has a somewhat cinematic quality to it, I was wondering, which films had the most impact on your musical approach?

It’s obvious that The Two Jakes film shows my ability for vertical development in a score that is more than a melodic ability. I love orchestras, I love the power of cliché to use an instrument for its vernacular abilities. They extend beyond the humor of a bassoon and the hands of a rarely employed studio session musician. I learned a lot from every film I did, whether it was a National Geographic or Harold Ramis picture. I just say that because Club Paradise came into view the other night in front of my grandchild, and as with any good picture the ability of the composer hangs on his adaptability to a scene. This is a deep topic, the business of film composition, so multilayered, but to say it means a hell of a lot to me and my loyal family is an understatement. Of course, my audio efforts - that is, the LPs like Song Cycle, etc. - all sound like they have a synthetic reality, maybe feeling filmic. The fact is, I love the atmospheres that orchestration allows, and I pursued it. While others who were given rock ‘n’ roll contracts spent their winnings buying real estate, I spent my money on orchestras to try to please the ear.

Relatedly, you worked on the soundtrack to the Popeye movie, and “He Needs Me” is your most popular song on streaming services today. Did you expect that soundtrack to have such staying power?

I knew that the discombobulated string arrangement I did for Shelley Duvall was durable goods. It captured the elasticity and pendular irregularity of Olive Oyl. It could’ve been given a better chance in the film, but on the soundtrack record and CDs, you can hear it, and it’s a great schizophrenic reality, as if I had heard Looney Tunes or Spike Jones as a boy and had no fear of abstraction.

You had a cameo in the second season of Twin Peaks. You’ve said you weren’t too familiar with Lynch’s work before then, but I know your friend Peter Ivers sang the Radiator Lady song in Eraserhead. Was that something you had been aware of?

I’m responsible for Peter Ivers having a record contract at Warner Brothers. We were very close from beginning to end in his dalliance with showbiz. But that had nothing to do with my appearance on Twin Peaks. As a prosecuting attorney in the final scene, I realized the judge was an actor I’d known decades earlier as a child in New York live TV. That actor was Royal Dano. I’ve seen him portray Lincoln more believably than Henry Fonda. He was a dead ringer for Lincoln. It was far out to be given a cameo part in an episode of Twin Peaks with a man I’d known in another version of myself, as a child actor.

When you started working with musicians like Rufus Wainwright and Joanna Newsom, did you view it as a career resurgence or just a continuation of the work you’ve always been doing?

I’m happy to say when Loudon Wainwright asked me to do something for his son, I introduced him to Lenny Waronker and my letter said “if you don’t wanna produce this guy, I do.” Lenny went on and got another producer, probably spent twice as much money as I could possibly have imagined at one Jon Brion, and they got to the point where they needed some tunes arranged. I did six tunes on Rufus‘s first record, so I ended up as an arranger, not a producer. As far as Joanna Newsom is concerned? I have equal respect for her ingenious music. There’s something, I would say, soporific - to use a word that Beatrix Potter used in Peter Rabbit stories - about 40 minutes of harp unaccompanied by anything but a striking voice. I use the same chamber orchestra that I use in such advances with budgets that are very difficult to deal with to make a group large enough to be small and small enough to be big.

You did arrangements for “Black Sheep” from Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story, which I think is one of the funniest movies ever. Was it surreal getting asked to work on something that was a very direct parody of what you were doing in the 60s?

I was willing to be the target when Mike Andrews asked me to bring comedic value to the piece, and musical humor is a very difficult thing. I took the opportunity as a discipline.

You’ve been very outspoken in your support for Palestine, which I’ve always appreciated. When did you first start paying attention to this issue?

I’ve gotten in a lot of trouble for condemning Zionism. As a matter of fact, my mother‘s uncle Bowman Foster Ashe was one of Winston Churchill’s great admirers, and gave him an honorary doctorate. I spent all my life admiring Churchill, but he created a big problem when he put a middle European Judaism into a historically Palestinian culture and their land without further thought. Churchill went from being a childhood hero of mine to one of enduring fragility as an icon that deserves reinspection.

Have you always had to deal with people telling you to shut up about politics and stick to the music, or is that something you’ve only noticed recently?

It’s always been with me. I was so grateful to Rufus Wainwright for doing “Black Gold.” Why? Because it’s my interest in ecology and activism. We all need to address this business of oil and world power in the White House in Venezuela in Saudi Arabia and how it’s metastasized into a religious foment, armed with an ancient theology, run amok. I’ve been so obsessed with big oil and want my work to be a clarion of protest against industrial abuse in the extinction rate and its rapidity that we now enjoy.