An Interview with Joe Boyd

In music, some people make one album and disappear, some stay around for a short while, some people live a whole life in music, and then there’s Joe Boyd. By the time Boyd was in college, he was already putting on performances by some of the most influential blues musicians of the early 20th century. Immediately after college, he worked for Newport Jazz Festival kingpin George Wein, managing European tours for the likes of Muddy Waters, Coleman Hawkins, Rev. Gary Davis and Sister Rosetta Tharpe. He was there in 1965 when Dylan went electric at the Newport Folk Festival. Then he moved to London and established the short-lived but legendary UFO Club, where Pink Floyd famously got their start. By the time the UFO Club shut its doors in 1967, Boyd was still 25. In the latter half of the 60s, he produced records by the Incredible String Band, Fairport Convention, John & Beverly Martyn, and a little folk artist by the name of Nick Drake. In the early 70s, he collaborated with Stanley Kubrick on the soundtrack for The Clockwork Orange and helped record the “Dueling Banjos” song from Deliverance. He was also a pivotal figure in “world music” becoming a thing that you more easily find at a record store, and produced one of my favorite R.E.M. albums Fables of the Reconstruction.

In short, he’s seen some shit, and he has stories to tell. His memoir White Bicycles: Making Music in the 60’s was described by Brian Eno as “the best book about music I’ve read in years,” and this past year he released his follow-up And the Roots of Rhythm Remain, an 800-page odyssey into musical forms that many in the West may recognize without having much context for. Impressively, Boyd never really had any formal musical training, and the fact that he was able to build such a storied life in music is a testament to the potential of deep listening. We talked for over two hours and I still didn’t have time to cover all of the bases, but we did find time to talk about producing Nick Drake, getting threatened by Alan Lomax, how the hell AMM ended up on bills with Pink Floyd in the 60s, and much, much more.

Huge thanks to Amelia for helping with the transcription, and for The Wire for making it possible for me to go to Big Ears.

I’m guessing you’re calling from London, correct?

That’s correct, are you in Chicago?

Yeah, I’m in Chicago. Have you spent a lot of time here?

I was just there, it was one of the early stops on my book tour that included Big Ears. I did an event at the Old Town School of Folk Music.

That’s right. I’ve been living in Chicago for almost three years now, but there’s a lot of these landmark places in musical history that I haven’t had the chance to go to. I haven’t been to Old Town, I haven’t been to the Jazz and Record Mart either.

The Jazz Record Mart is a very important place in my early musical life.

Yeah, I had read that you met Mike Bloomfield there. In the 60s or 70s or whatever, were you coming through Chicago a lot for -

‘50s and early ‘60s, yeah.

Were you going there for concerts and shows you were putting on and stuff like that?

No, no. This was when I was a kid. I had cousins there. We had family, relatives. I think that was the main reason. Then once having discovered The Jazz Record Mart and made friends with Bob Koester, who was the owner, my brother and I and Geoff Muldaur went there just to hang out, I think that’s when we met Mike Bloomfield. That was in 1961, something like that. Then I went there on my way to the West Coast during a year off, or what ended up being a half year off from Harvard. I stayed there on the way and then I went out there and visited Muddy Waters before I tour managed him. That was my first real proper job in the music industry after I got out of college in 1964. I then went there with Paul Rothschild when he signed Butterfield [Blues Band] to Elektra, so there was a lot of Chicago and then for a long time there was very little Chicago. It was a city that was very important in my young years, but once I moved to London in ‘65, I rarely ended up in Chicago and haven’t been there much in all that time since - maybe four or five times.

Was it refreshing to come back for the book tour? Did you go to any of the old places you used to go to?

Not really. We didn’t really have that much time, but I love the Old Town School. I did an event there about 15 years ago. I did a tour with Robyn Hitchcock where we did a double act where I would read from White Bicycles and always include a reading about a song or an artist performing something and then Robyn would sing that song. We’d go back and forth, read a bit, sing a bit and we did that. We did two shows at the Old Town School back in 2011, I think.

That’s amazing. I know you’re currently in London and you obviously spent a lot of formative time there, but I know you went back to the United States. Did you end up moving back to London years later?

Basically I moved to London in the autumn of ‘65 and in the 60 years since then there have only been about two and a half years when I didn’t have a place in London. Many of those years I was sort of back and forth between London and L.A. and then back and forth between London and New York. Since 2002 it’s been just London.

OK. One of the first questions I have is what made you want to be a music producer as opposed to just being a musician yourself?

Well, my grandmother, my father’s mother, had been a classical pianist and taught classical concert pianists, she prepared them for their recitals. I used to sit under the piano when I was three or four and listen to her. I took lessons starting when I was six or something, but I never felt that I was a performer, I just loved music. I don’t know whether I just didn’t have the discipline to practice or whatever, but I was much more involved in listening to it than in performing or playing it. As I grew up, my circles of interest expanded to include old blues, old jazz, rock and roll, classical music. My mother had Marlene Dietrich and Carmen Miranda records and Edith Piaf records, it all just spiraled around. And I read. The kind of eureka moment was when I read a book called The Country Blues by Sam Charters. He writes about the early process of recording blues singers in the South and the character of Ralph Peer loomed very large in that book. For a while I was sad that I felt I’d missed a great moment. That, you know, the world had changed and I couldn’t be Ralph Peer. I eventually realized I could still be Ralph Peer, even though things weren’t as wide open as they were in the 1920s, that in a way the early and mid ‘60s were kind of like that period. It was pretty wide open, in that if you had an idea, you pushed on the door and just walked through and started doing stuff. Once I realized that it was conceivable to be a record producer, it was clear in my mind that that’s what I would be from about age 16. That was also the same era where you had a lot of people rediscovering all these old blues musicians. They would hear somewhere that they lived in some small town in the South and people would travel out to find them and record them and everything like that. That was a thing that was happening at the time.

Early on you were putting on low-key performances for people like Lonnie Johnson. Did you pick up the basics of working on sound from putting on these concerts?

Well, basically, I think the most important thing about learning to produce a record is listening. When I first went into a studio as a producer, I had listened to a fantastically high amount of music. I always had music on. I would do my homework with records playing. Me and friends of mine or me and my brother would sit around playing records obsessively, discussing it, listening to it. And then I was very fortunate to have, when I was at Harvard, the scene around Club 47. The folk club in Harvard Square was very fertile, full of great characters and energy and a burgeoning scene. I met a guy called Paul Rothschild there who was at the time a salesman for the local record distributing company, he was a real jazz buff. He sort of stumbled on Club 47 and was intrigued and started recording some of the musicians there and putting them out on his own label. I got to know him and I came to sessions where he was producing and he would ask me to keep track of the takes on the back of the tape box and help him out moving microphones around and stuff. That was a fantastic, door opening experience because Paul to me was, you know, so sad that he had such a short career, dying of cancer at a youngish age. His productions are still, I think, some of the greatest sounding records of the rock era. Particularly The Doors records and Janis Joplin. To be in that in the control room with him and get used to the way things were supposed to sound, that added to my experience of listening. I was very fortunate in my early time as a producer to have great engineers. A lot of people who are producers today started out as engineers. That was true back in the ‘70s and the ‘80s. A lot of engineers migrated over to being producers and that was never my way into that. I learned a lot about the technical aspects, but I didn’t have the temperament or the knowledge to be an engineer. Most producers back then in the ‘60s were like me, they were just listeners who had worked with engineers. I always had a vision in my head of my record collection, all the records I’d heard, and I wanted to make sure that any record that I was producing would be good enough to fit into the shelf beside all the records I’d grown up listening to. I felt I didn’t want to make records that were of a lower strata of musical quality than the things that I loved. I think the most important thing for me always was just listening and listening and listening.

Yeah. It’s interesting because based on that description I can see a connection between your approach to producing music and your approach to writing about music. It seems like you’re not overly concerned with the technical aspects and I know with your writing, like the book that came out last year, you weren’t trying to do an academic type book, you were trying to write from the perspective of someone who just loves the music.

One of the things that I discovered as I was writing, I mean, it sort of came to me at a certain point, I realized that my process in writing the book reminded me a lot of mixing because I’d digest a bunch of research and then I’d write a few pages of text and it would be very rough and very raw and full of things that didn’t sound very good and sentences that were too long and too many adjectives. And then I would sit there and start pruning, taking words out, taking sentences out, finding a better way to describe something, tweaking it at the edges and slowly getting it into a shape where I could actually enjoy reading it back to myself. It felt very much like mixing, like taking a track that had been recorded in the studio and moving the guitar around until it sounded in the right position and tweaking with the EQ until the drum sound fit with the rest of the music and the attention to detail that helped bring it into form where you could sit back and say, yeah, OK, that sounds pretty good. I felt that the process of writing touched the same parts of my brain that mixing a record did.

That’s really fascinating. I was wondering who - you mentioned, Paul Rothschild - when you were getting into music, who were your favorite producers or engineers or people like that?

Back in the ‘60s or even before in the ‘50s when I was listening to the first records that really hit me, I wasn’t so conscious of who were producers. That’s why that book by Sam Charters was so revelatory. I said, oh, there was a guy putting up the microphone and bringing the musician, oh right that was Ralph Peer. So I think Ralph Peer was obviously a very important figure for me. And then, of course, the giant that loomed over anyone getting into music in the early 60s was John Hammond, because he had this incredible career, signing Billie Holiday, Count Basie and then Dylan and Leonard Cohen and Springsteen, you know. I met him and he took a liking to me and would invite me up to the Columbia Records office and we’d sit around and talk about music and he’d tell me stories about going to the Apollo Theater when he was a teenager in short pants and stuff like that. He was definitely right at the top of a list of great producers. Obviously, I have to say Bob Koester from Chicago, who ran the Jazz Record Mart and Delmark Records. He was a cranky, curmudgeonly, very narrowly focused jazz and blues guy. But I think some of the records that he made, particularly Piney Woods Blues by Big Joe Williams, are wonderful records, really great records.

He had the wit to, you know, take a country blues artist like Big Joe Williams, who’s very raw, who played with a nine string guitar and was very country in many ways, and put him with a bass player like Ransom Knowling, who was a very urbane, sophisticated bass player from the South Side of Chicago and come up with this record that sounds so good. He was an important figure. And then for six months I worked in LA. Koester gave me an introduction to Les Koenig, who was the executive who ran Contemporary Records in LA. I was like an office boy, errand boy, doing whatever needed to be done. I would turn up sometimes, maybe once, sometimes twice a week, and Les Koenig would say, ‘Ok it’s time to get the piano out today.’ There was a shipping room in the back and a piano covered in a padded quilt over in the corner. And I’d roll the piano out, take off the quilt, lift up the lid, and a piano tuner would come in and then late in the morning, the back door bell would ring and in would walk Philly Joe Jones with his drum kit. It would just be fantastic. I would sit there and these amazing records would unfold. One day, Ahmet Ertegün came to visit, and so I met Ahmet. Ahmet was one of my early heroes, a guy who produced early R&B, what they called “race records” in those days. Jazz records, blues, and then, you know, sort of morphed. [Ahmet] was the one who recorded Ray Charles and so many great, game changing records. [He had] that ability to work both sides of the street. He was a kind of nerdy collector and aficionado of great music, but they also had hits that went into the charts. He was always looking for that, and I was fascinated by him. There was a whole galaxy of people that I was so fortunate to be able to rub shoulders with, people like Chris Strachwitz from Arhoolie. Then when I went to Britain, I ended up staying for a while in London on the sofa. I slept on the sofa of a guy called Bill Leader, who was the leading producer of very traditional folk music records. He was the main producer for Topic Records. A lot of his records were a cappella. The Watersons recorded in his kitchen.

He was the opposite of Paul Rothschild in the sense that he wasn’t very technically concerned, you know, he was much more about getting a performance out of people. In his, he used a two-track Revox to record and would just set up in whatever kitchen or front room was available. But the records sound pretty good. He had a very good sense of where to place microphones, but he was also really concerned with the moment and the artist and the interaction between him and the performer and to inspire people and challenge people. And the way he was recording, whatever happened in the next 30 seconds was it. It was never going to be overdubbed or tweaked or edited or fixed. That was it. You could do another take maybe, but you wouldn’t want to do a long a cappella ballad more than twice, so it all had to be there. I learned a lot about the process of working with artists from Bill Leader. And then when Paul Rothschild helped me get a job with Elektra Records opening their London office and we were in Soho and, you know, you were surrounded by music publishers and managers and record labels. I met people like Denny Cordell and became good friends with Denny. He was another guy that I found very inspiring. He was the guy who produced “Whiter Shade of Pale” and The Move and Joe Cocker and started Shelter Records later when he moved to California. I was so lucky to be around a lot of those great figures.

Yeah, absolutely. You mentioned Bob Koester, I heard about Delmark probably because of those classic records by Magic Sam and Junior Wells and people like that. But I also got really deep into it when I started listening to all the legendary free jazz records on that label. I had read somewhere that he didn’t even like free jazz, but he still recorded all these albums and released them, which is really fascinating to me.

Yeah, you know, It’s funny, I never really talked to him much about the modern jazz he recorded. I had a very close relationship with him for a while, because I started a distribution company when I was at Harvard, and I would distribute Delmark and Arhoolie and Origin Jazz Library and Folk Lyric, Folk Legacy, etc. The Delmark catalogue then was, to me, two-sided. There was Sleepy John Estes, Big Joe Williams, and as you say, just beginning to record Junior Wells and Magic Sam. And then he had New Orleans content. He had a great series of recordings by George Lewis and his band. And it was only just as I was leaving Boston and sort of handed the company over to somebody else that he began recording some of the cutting edge modern musicians in Chicago, some of the people associated with the Art Ensemble [of Chicago] and that kind of world. But I never actually distributed those records because they were just coming in when I left. I never really talked to him at length about it so I don’t know what his feelings were about it.

Going off of what you’re talking about with how he paired Ransom Knowling with Big Joe Williams and things like that, one of the things I learned from reading White Bicycles was how involved you were with putting together like the lineups of different groups for the tours you were promoting and managing, like The Blues and Gospel Caravan.

Well no, that was sort of a unique, incredible situation where I had this sudden window of opportunity. Manny Greenhill in Boston said that George Wein was looking for a tour manager for this tour that was leaving in two months and I wanted to go to Europe. To me, Europe was where people appreciated American music much more than Americans did. I wanted to go there also because I liked the idea of going to Europe but I didn’t know how I was going to survive over there. I had completely unrealistic ideas about it. Anyway, I went down to New York to be interviewed by George Wein and after about a half an hour he made some reference to the fact that they needed to figure out the lineup for the tour that was just two months away and they hadn’t really decided whether there was going to be a drum kit and whether there was going to be a bass player. You know, I think at that point, there was enough money in the budget for, Mississippi John Hurt was supposed to be on the tour, but he pulled out because he became ill. So George just said to me, “Could you find a bass player?” and I said “Yeah” because I immediately thought of Ransom Knowling because of Koester telling me how great he was and how great he did with Big Joe Williams. So I said “Yeah, I can find you a bass player” and George said, “Well, there’s a phone over there. Go sit down at that desk and get to work and get us a bass player.” It turned out that my interview day was my first day at work. That connection with Koester sort of made me sound like I really knew what I was doing. And of course, Ransom turned out to be a real tower of strength on the tour. That was the only example. The next tour with George was all these jazz groups that I had no business making lineup suggestions to, but I always had an opinion. Particularly about rhythm sections, I would always listen for that and listen for how groups fit together and how they sounded but I was never one of those guys who acted like a puppet master and put together a group. Sometimes I make suggestions like suggesting that Mike Bloomfield could join the Butterfield band and somehow it worked out and became a great combination. When Paul Rothschild and I first heard Butterfield it was just Elvin Bishop on guitar. It was great. I loved Elvin Bishop, but he wasn’t a lead player. He wasn’t a guitar hero. I’d just been in England where everybody was talking about Clapton and Jeff Beck. That was a real totemic role to fill, you know, the lead guitar player.

In White Bicycles, you draw a pretty clear distinction between rhythm & blues, rock & roll and rock, and you described Dylan’s Newport performance in 1965 as the birth of rock. What would you say separates rock from these other genres?

Well, one reason why I can say that is because before then, nobody ever used the term rock. It wasn’t the term that you would hear. There was rock & roll, there was, you know, pop music, there was rhythm & blues, but I think what was kind of hard sometimes was looking back and putting yourself in that time and seeing what a revolution it was, what Dylan did. First of all, coming out onto stage wearing - I mean, Dylan was very careful and conscious about the way he dressed but he liked looking as if he threw on whatever was beside the bed when he got out of bed that morning. This was at a time when the Stones and The Beatles were still wearing nice jackets and sometimes even a tie when they went on Top Of The Pops, or Ready, Steady, Go. Even then, The Beatles and the Stones in the spring of 1965, if you look at the lyric content of their songs, it’s largely about sex and love. It’s boy - girl stuff. And Dylan comes out on stage looking like nothing like a performer coming out for a big important gig and he’s singing about, “I ain’t gonna work on Maggie’s farm.” I mean, what’s that about? Where is that? Where do you get that from? What’s that mean? How does that relate to the girl I’m dancing with at the rock & roll gig, you know? It doesn’t. I think that Lennon and McCartney have both talked in interviews about the huge effect that Dylan had on them and their freedom to write lyrics about things that weren’t the same as what they’d been writing before, that it opened doors that they could walk through. And I think also the rhythm section, that Howlin’ Wolf rhythm section - Sam Lay and Jerome Arnold - laid down a powerful beat that was, you know, I think one of the things that I hadn’t really thought that much about, but because of the film and because of the anniversary of Dylan going electric and all that kind of stuff that’s happened in recent years, I’ve had to talk about that night and how I perceived it and how I remembered it as the production manager. I realized that one of the things that people haven’t talked about much is that the film, A Complete Unknown, is pretty good with time. It looks right, mostly, but I remember I spotted two anachronisms in that film. One of them was the zebra crossings on the streets in Greenwich Village, there were white lines painted in the street for pedestrians to cross. You didn’t have that in the early ‘60s. What you also didn’t have, you didn’t have any stage monitors on the stage, there’s a little speaker in front of Dylan when he’s on stage at Newport in the film, but that didn’t exist. There was no such thing as stage monitors so you had to really hear yourself through the PA speakers that were off to the right and left. And there was no direct input from amps to the PA system. There were some microphones in front of the guitar amps and the bass amp, and maybe one or two mics over the drum kit, but I don’t think we had that many mics. We probably had five or six mics tops. And Bloomfield wanted to be loud, you know, he was cranked up and he was very excited. At the soundcheck he had his amp turned quite loud, and Sam Lay is a very powerful drummer, so you had this very loud rhythm section, and you had to raise the volume of the vocals to get him over what was happening with the rhythm section to be audible, because there wasn’t enough control of the volume to really balance it unless you just simply raised the voice higher and higher to get it over that sound. The power of it became part of the signature of that kind of music. You had a mixture of stage attitude being completely anarchic or different or less formal, less show business than it was before, the lyrical content being much more abstract, much more personal, much less formulaic than it had ever been before. And then you have the sound, which is this mixture of Chicago blues with a big ego white boy attitude. On top of that, you put all these things together and you have a kind of new sensibility that became the signature of rock, what we know as rock. That’s why I think it’s safe to call that moment the beginning of that movement.

It makes sense to me because I do think of rock and rock & roll as being two different things. Rock & roll I associate with Chuck Berry and that generation, and rock I associate with the generational shift in the 60s.

Yeah, and the things that are a bit hard, that are sort of in the middle, are things like The Kinks, who had a very aggressive attitude and obviously played loud, and they became part of the template for rock. But back when they had their first hits in ‘64, when “You Really Got Me” came out and they went on Top Of The Pops, they were a pop group. They dressed nicely, they played three minute songs, three and a half minute songs tops.

What’s funny to me about the Newport performance is that it was Dylan’s first performance playing with an electric band, but Bringing It All Back Home had been out for a few months by that point, if I’m not mistaken. So it makes me wonder if people listening to that record assumed it was just a fluke, like he was just toying around with the idea of having an electric band and didn’t realize he was actually going to go all the way with it.

I think it was complicated, because I think people were definitely - “Like A Rolling Stone” was on the radio, it was a hit. And The Byrds’ “Mr. Tambourine Man” was on the radio. It was all over the place, but I think because he’d never performed that way live and because this was Newport, it felt like an enclave. The whole aesthetic of Newport was college kids with guitars sitting in with guys from the Appalachians with their fiddles. It was an acoustic bubble. And as you know, somebody sent me a photocopy of a postcard which Pete Seeger sent to Dylan afterwards in which he says, “I didn’t have a problem with you playing electric at Newport, I just had a problem with the fact you couldn’t understand the lyrics.” He said Howlin’ Wolf played Newport the year before with his band. So there’s no, like, “you can’t have electric guitars on stage at Newport, you can’t have a drum kit on stage at Newport.” But I think it was clear that what Dylan was doing and what he represented that whole weekend, and what The Paul Butterfield Band represented, was that there was a challenge to the old guard. There was a culture clash moment, a generational clash moment. What really was happening when I - again, this is something I reflect on later, it wasn’t a thought I had at the time - what was really invasive about what Dylan did, was that it brought Tin Pan Alley careerism to Newport. This was like Top 10 stuff. This was the birth of something that would lead to stadium shows, that was going to open up this huge audience. It was mass market stuff. Suddenly even Dylan, when “Blowin’ in the Wind” was covered by Peter Paul and Mary and it got to number one and all of that. Everybody could sense there was no hiding from the fact that this was a big change and that this was very intrusive. It did kind of destroy the folk scene and it destroyed the jazz scene and I think you can parse it out, like, “Was it the volume? Was it the distorted sound of the voice? Was it the attitude? Was it the clothes?” Whatever it was, a lot of these messages are sent in much more subtle ways. There was something fundamental. Among other things, it was a fact that the old guard was freaked out by smelling pot. In 1964, you could probably walk through the Newport Folk Festival during the afternoon of Saturday to all the different workshops, put your nose in the air, and you would almost never catch a whiff of marijuana. In 1965, you walk through on Saturday afternoon around the thing and you catch a whiff everywhere [laughs]. I think that also freaked out the Lomaxes and the Theo Bikels and even Seeger. I think you can isolate certain elements, but overall, ‘It ain’t what you do, it’s the way how you do it’. It was the attitude, it was the style. I mean, Dylan’s wearing those - him and [Bob] Neuwirth, him and Al Cooper wearing those silly polka dot shirts around on Saturday [Laughs] and these boots from an 8th Street shoe store in Greenwich Village. It was all new. We’re sweeping away the old aesthetic, whether it’s the kind of heels on your boots or it’s the leather jacket you’re wearing or it’s the sound of your guitar becoming electric, whatever it is, we’re getting rid of it and we’re doing something new.

Yeah, for sure. I’m jumping around a bit to the UFO club years. One of the biggest questions I had going into this interview is how did AMM end up playing shows with Pink Floyd?

[Laughs] I’m not sure I can, I don’t have chapter and verse. I have a vague memory that that happened once. But I couldn’t tell you where or when. But AMM, the recording that I organized for the record that came out on Elektra of AMM was brought to me, suggested to me, by my friend, John “Hoppy” Hopkins, who was the kind of leading figure of the underground scene in London and Peter Jenner, who was at the time teaching at the London School of Economics and who would later become the manager of Pink Floyd. They loved the kind of stuff that AMM was doing, they were big fans of avant garde jazz. Hoppy was a friend of Bernard Stollman who ran ESP, and Jenner was sort of working with AMM to help them organize some things at the same time that he was managing Pink Floyd. I’m not sure whether Syd Barrett heard Keith Rowe live for the first time, or whether he heard the record that we made, or whether he heard them in rehearsal, or I don’t know what. But anyway, Syd heard AMM, and this guitar player for AMM, Keith Rowe, who used a lot of objects and noise making things on the guitar, I think that was a very important step for Syd Barrett and the formation of his approach to the guitar. Pink Floyd were a long way from AMM in terms of what they were doing musically, but you can hear that avant garde edge being an influence in The Floyd.

I also know that Keith Rowe was doing a lot of stuff with shortwave radio and I think I’d read somewhere that that kind of inspired [Syd Barrett] for the first song on Piper At The Gates Of Dawn to incorporate that into his music.

Syd was a magpie, he would pick up things. I’ve told this story before, but I still love the story. I didn’t know it at the time, I only read it years later. In the ‘80s or ‘90s I was cleaning out some files and I came across an interview with Pete Jenner and he talked about - there was a moment when I was still working for Elektra and Jenner had the idea that Elektra might be interested in signing The Floyd but he also was worried that Elektra was too folky. This was just at the moment when Elektra had released that first wave of rock, you know: The Doors, Love, Tim Buckley, and The Butterfield Band. So I gave Jenner promo copies of those four albums and he called me up the next day and said, “Wow, those records are great. I love that. I’ve told the group about what a great label Elektra is.” And then in this interview that I read years later, he says that he went to a rehearsal of The Floyd and at the end of the rehearsal he sat down with Syd and he told him about this record by this group Love. He said, “I’ve got to play you this record. This record is so great, you’re going to love it.” He said, “The first track, you’re going to love the first track. It’s this song called ‘My Little Red Book’” and Jenner, who can sing about as well as I can, which is not at all, sang to Syd, “I just got out my little red book the minute that you said good-byyye” and Syd just turned to him and said, “Hang on -” and he went and got his guitar and he said, “Do that again” so Jenner went, “I just got out my little red book the minute that you say goodbye” and Syd then played that, which is a kind of distorted, out of tune version of My Little Red Book by Burt Bacharach, he played it on the guitar and that is “Interstellar Overdrive”.

I actually hadn’t heard that story before. That’s amazing.

Yeah, if you listen to “Interstellar Overdrive”, that’s it. It’s kind of a weird, distorted version of the first line of “My Little Red Book”.

Yeah, now I think about it, that does make a lot of sense. That’s fascinating. Something that I guess ties in the other elements is that I read somewhere that one of the reasons AMM liked the idea of making an album on Elektra is that they had released some Japanese classical music as part of the Nonesuch Explorer series. It’s really interesting to me, because I guess it relates to some of the things you’ve written about in your more recent book. I feel like there’s a degree to which this idea of “world music” is a thing that I don’t think people really seem to talk about until the ‘80s, but there was also a thing where these non-Western musical forms were a major undercurrent in ‘60s counterculture, and that’s something that’s really fascinating to me.

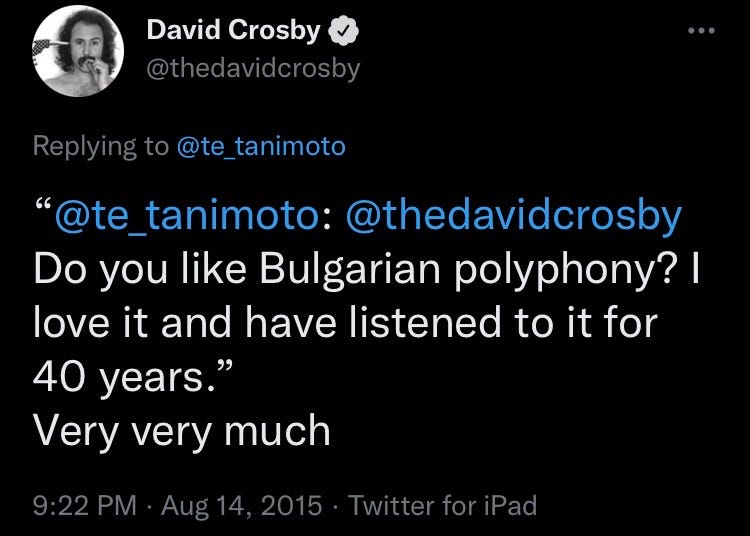

Yeah, I think Allen Ginsberg and Alan Watts and these figures were very important in leadership roles in the overlap of the beatnik era into the hippie era. They revered that culture and Morocco, India, Japan were all destinations for seekers, for people looking for another way of viewing our civilization. So the music obviously would sort of enter that. As I talk about in the book, one of the one of the key things that happened in the middle of all of this was the Bulgarian Choir, you know, it was one of those things you could get stoned to, put the headphones on and listen to, like Ravi Shankar. You listen to the Philip Koutev Ensemble. And people just found this music, it was context free. There was no idea what these lives were like, or what the culture looked like or felt like or anything. It was just sound, it was just music that was detached from context and therefore was free to travel. And people picked up on it. You’ve probably read interviews with David Crosby where he talks about the huge influence of The Bulgarian Women’s Choir on the way he found harmony voices, harmony parts with The Byrds and Crosby Stills Nash & Young.

I actually haven’t. I knew that he was a fan of that kind of music. I didn’t realize it was like an influence on him.

Well, yeah, he said that gave him a lot of ideas. And I think Joni Mitchell loved that record too. And, you know, on “Rainy Night House,” or whatever it’s called, I think that’s the name of the track, she does overdubbed harmonies that are totally Bulgarian, they’re like lifted right off the Koutev Ensemble record that came out on Elektra, Nonesuch.

I guess I wouldn’t have pegged that because I know that the Koutev Ensemble record came out in the ‘60s but most of the records that I know about, those kinds of Bulgarian choir music, I mean I think the main one I know about is the -

Le Mystère des Voix Bulgares

hank you for pronouncing that, I’m terrible at pronouncing French [laughs]. But yeah, that’s the big one I know about and that was later.

That was like, 12 years later. The first Koutev Ensemble - I described the scene in the book - Albert Grossman, Dylan’s manager, was in Paris, and he was at somebody’s house having dinner. And they put on this 10-inch LP on the Le Chant du Monde label and it was The Koutev Ensemble, and Grossman flips out. He grabs the record, looks at the back of the record and sees that the Le Chant du Monde label has an office in Paris, so he writes down the address, goes there the next day, walks into the office and negotiates a deal to buy the North American rights to that record for like 2,000 bucks. And he gives them $2,000 and walks out with a copy of the master tape and he goes back to New York, this was in ‘65, he goes back to New York. He had just taken on The Butterfield Band as manager and he was negotiating their deal with Elektra. So he and [Elektra founder Jac] Holzman are haggling and finally Holzman says, you know, this is my final offer. And Grossman says, “Okay, I’ll accept that on one condition: you have to put out this record.” He hands over the Kutev record and, of course, Holzman listens to it and says, “This is great. You don’t have to twist my arm to release this. This is great.” So it’s all tied in with Butterfield, all the stuff we were talking about earlier leads directly into this opening scene of my Soviet chapter where this record comes out and then Grossman’s license expired. I don’t know, it was a five year license or an eight year license or something.

Anyway, by the mid ‘70s, the record was deleted so people had kind of forgotten about it. Then in the middle ‘70s, Marcel Cellier, this eccentric Swiss guy, claims to have recorded them himself but he didn’t. He just bought the rights off Bulgarian Radio for their women’s choir and he put out this record and called it Le Mystère des Voix Bulgares. It had a certain success in France and Germany, but it was only available as an import in America and Britain until 4AD Records, which was the Cocteau Twins’ label, licensed it from Cellier and put it out in England. And John Peel started playing the shit out of it. It became this huge phenomenon in 1985 or ‘86. It was another 10 years, it had been available just in France and Germany. You had these 10 year gaps between these sorts of moments for Bulgarian choirs.

That’s kind of a funny recurring thing in both of your books is that it seems like John Peel is the one person who latches onto these things. He was the one person who was playing Nick Drake. Did you know John Peel at all?

Yeah, I knew John. I wouldn’t say I was a close friend, but he was great. He was very, very friendly and very supportive and he was the one who told the 10,000 Maniacs that I should be their producer. That’s how I ended up doing the first 10,000 Maniacs record. He was always very funny, very nice, a wonderful guy. Very open, you know. In a way, one of the weird things about this transatlantic music industry is, by the late ‘60s in America you had this freeform FM radio everywhere. We didn’t have anything like that in Britain, the closest thing to it was Peel. And one of the things I discovered, somebody told me this recently that I got it wrong in the book, or I just didn’t mention it, but the fact is that Peel had gone to America and worked in American freeform FM radio, so he understood what that meant. He came back to Britain and ended up working on a pirate radio, one of those offshore ships, and would do the late night thing that nobody else wanted to do. He called it The Perfumed Garden and it was the show that broke The Incredible String Band. He played 5,000 Spirits all the time on The Perfumed Garden and that’s what lifted that record into becoming a big success. It was just part of the landscape to me, John Peel, Perfumed Garden and all of this stuff going on. I later discovered that Perfumed Garden was only on the air for like three months or something in the summer of ‘67 and then the government clamped down. There was a sort of deal done where they made it punishable by law to advertise on a pirate radio. But at the same time, the BBC agreed to open up Radio One and make it more open, more youth oriented and they hired John Peel to do his show late at night. So you had The Perfumed Garden suddenly, but originally it was only once a week, I think. Eventually it got to be more often but he was always open to playing Nick Drake, he loved Fairport, Nick Drake, John Martyn, all the kind of stuff I was doing.

One of my favorite groups that you produced is The Blue Notes, who I love. In both of your books, you talked about how they were kind of given like the cold shoulder in the London jazz scene. Musicians in that scene were kind of threatened by them or whatever. It’s interesting because looking back at the musicians that they individually worked with, particularly in Chris McGregor’s Brotherhood of Breath, I feel like they’re working with a lot of the best people in that avant garde jazz scene in London. Who are the people in that scene that didn’t understand them like that? That’s what I’m curious about.

Well, I’m not - certainly they never got any more gigs at Ronnie Scott’s, that’s for sure. I think a lot of what I say is based on what I understood from talking to Chris McGregor and Dudu Pukwana and also from a brief experience of trying to get them work. You know, I was their manager for a while and places that would book Tubby Hayes and Ronnie Scott, and a lot of the sort of major figures of the modern jazz scene in Britain - we struggled, we couldn’t get any traction to get gigs for The Blue Notes. To be fair, and I do say this in the book, I think the group probably didn’t handle the situation very well. I mean, they drank a lot. And the word would go around the circuit that they could be a little hard to control and I think there’s a lot of racism in that. This idea that once you get that tag stamped on you, that there’s a group that’s mostly Black, that aren’t easy to deal with, that are stroppy, they get drunk, that they’re kind of scary, people kind of avoid them. It was very difficult. But I think my understanding of what went on, as I say, I’m not going to give you names of individuals who said anything bad about them at a certain point, because I don’t really have that. But my understanding of the jazz scene in Britain at that time was that it was very locked in to America. The kind of archetype journey of a jazz musician in Britain was Ronnie Scott, who was a young, eager sax player who worked as a sailor on a boat and ended up going to jazz clubs in New York and jamming with people and then came back having honed his chops in America. He was a perfectly decent bop sax player, and an awful lot of what happened in British jazz circles was about being a reflection of American jazz. And then you had, I think, what’s his name, the piano player who did a suite based on Dylan Thomas…

I feel like I know who you’re talking about, but I’m having trouble remembering [Editor’s note: it was Stan Tracey].

JB: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Anyway, there were movements to try and carve out a British character to jazz, but still I think the way that you made a name for yourself in the British jazz scene was by being a pretty good version of an American jazz guy. And I think the Melody Maker, which was the Bible of weekly newspapers of jazz, were skeptical of Ornette Coleman, they were skeptical of the Ayler brothers, you know, this kind of weird shit that was coming down the road. I mean, they never wrote about AMM [laughs]. So when these South Africans arrived that were doing something that was vaguely connected to Albert Ayler, that was connected to Duke Ellington, but was full of all these things that had to do with South African music, with township jazz and folk music, it was so fresh. I remember walking into the first time I ever heard them just being completely blown away by this. It was so unique, it was like nothing I’d ever heard before. I think for a lot of people it was threatening, because it threatened all the assumptions that British jazz was based on, which is that you were trying to be junior Americans, sort of. These guys were saying, “we don’t give a shit about that. We’ve learned a lot from America, but we want to be South Africans.” I mean, Chris McGregor and those guys loved Ellington, but they also loved the Ayler brothers, so it was very confusing to people. I think the Brotherhood of Breath record that I made just before I left to get moved to California, it came out after I’d gone, that record was so powerful that nobody could ignore it. I think particularly in France and around the continent, that record had a big influence.

Your new book, The Roots of Rhythm Remain - I’ve been trying to read as much of it as I can, I haven’t gotten to the Eastern European chapter yet unfortunately - but I read the South Africa chapter and one of the biggest discoveries I had from reading that book was The Manhattan Brothers, who I don’t think I’d heard of before. I listened to one of their albums after reading that and I loved it. I also didn’t know that they had inspired “Davashe’s Dream” either. Did the South African jazz musicians have a different attitude towards the popular music of their country than the jazz musicians in the U.S. and Europe at that time?

Yeah, I mean Davashe wasn’t in The Manhattan Brothers, but he wrote that song that became one of their big hits that was translated into English that I heard on Bob Horne’s Bandstand in 1956, you know [Editor’s note: Mackay Davashe wrote “Lakutshona Ilanga,” later translated into “Lovely Lies”]. And I think for them, particularly Black South Africans, there was a unity. I think what went on at Dorkay House was definitely not the same as what was going on in small provincial townships in rural South Africa for sure. You didn’t have avant-garde jazz, but there were centers of real exploratory jazz in Cape Town, for sure, in Port Elizabeth, in Durban, and certainly in Johannesburg. It would be the same thing if you ask Malachi Favors and Lester Bowie what they think. I mean, Lester Bowie was married to…

Fontella Bass?

Yeah, Fontella Bass, who had an R&B hit. There’s not a separation. I think most avant-garde jazz musicians in America, if you ask them what they think of James Brown, they love James Brown. They love Al Green, they love Willie Mitchell and The Memphis Horns, and so the fact that they are taking elements of that and moving out into some different zone with it doesn’t mean that there isn’t a strong connection. I think the connection between what The Blue Notes were doing and The Manhattan Brothers is similar to the connection between the Art Ensemble of Chicago and Motown or Chicago R&B or James Brown or more likely Parliament Funkadelic, you know.

Yeah. That is the thing I’m really fascinated by, because a big part of why I’ve gotten deeper into the ‘40s and ‘50s rhythm & blues type stuff is just hearing about so many of the best avant-garde jazz people, like Ornette Coleman and Albert Ayler, and especially Sun Ra who I know played with Wynonie Harris at one point. They all have a connection to that music, and you can see how the rhythm & blues music influenced the avant-garde. A lot of those records have this kind of screaming saxophone sound that you wouldn’t have heard anywhere else.

And there’s a strong cultural connection. I have a dim memory about Mingus putting together his band and wanting to have somebody who had experience of being on the road with R&B outfits. What was his name, Mingus’ drummer for a long time…

Danny Richmond?

Danny Richmond, right. He’d been on the road with R&B outfits and somehow that worked. When I worked with Defunkt in the early ‘80s, the guy who produced the first record, which I picked up for my label as a finished record, was the third Bowie brother, Byron. That family was a very middle class family from St. Louis, you know, Byron had master points in bridge and would go skiing on his holidays in the winter and he worked as a music director for Natalie Cole and the Dells and people like that. When we were putting together a band to go to Europe we had to get a new drummer because the drummer that we had that they had on the first record was doing something else. And I don’t know if you ever heard, there was a 12 inch single that I recorded in London at Sound Techniques with Defunkt, “The Razor’s Edge”. That was with the band that we put together to tour in Europe. That was the best version of Defunkt ever in my opinion, because Joe wanted to hire this guy who eventually played with Defunkt a lot, who was from New York and was a great kind of Billy Cobham type drummer. And Byron said, in all of his work as a musical director, his one rule that he never violates is you never hire a drummer who was not born south of the Mason-Dixon line. It’s just different. It’s in the pocket differently. And you need that as the basis. No matter how out you get, you need that rhythmic sensibility at the foundation of what you’re doing.

Going back to the UFO Club, when I was reading White Bicycles I looked up the names of the acts that I didn’t recognize who had performed at Rainbow Club and one of them was Exploding Galaxy, which I found out included Genesis P-Orridge from Throbbing Gristle and Psychic TV. That was crazy to me. Were you interacting with Genesis in those days at the UFO Club?

You’re telling me something I never knew

Really? I mean, I know a lot of those people were in that world of the ‘60s and ‘70s.

Yeah, there are all sorts of people that pop up in different guises later on who knew who they were at the time, you know?

Were there a lot of people at the UFO Club who went on to do bigger things?

Yoko Ono. I mean, as you say, some of them, I don’t know who they were at the time, and they pop up to be something else later. There were a lot of people who burned and faded, like Arthur Brown.

One thing I wanted to ask about Nick Drake that you mentioned in White Bicycles is that there’s all these Anglophone singer-songwriters who have cited Nick Drake as an influence, but don’t actually sound anything like him. I think you said something about how the only ones who did kind of remind you of Nick Drake turned out to be unaware of him. Who are the singer-songwriters that actually did kind of remind you of Nick Drake?

Well, I mean, I think if somebody too much reminds me of Nick Drake, it’s because they’re trying to sound like Nick Drake, which isn’t that interesting. I suppose the artist that I had in mind when I said that is a group called Hank Dogs.

Really? I’m not familiar.

Okay, well, look, make a note: Hank Dogs. The two great records I put out on Hannibal are not on Spotify but I think they’re on YouTube. Immediately when I heard their tape I thought it sort of somehow evoked something that felt similar to the moment I first heard Nick. And then I asked the woman, the lead singer and songwriter, if she’d listened to a lot of Nick Drake records and she said, “Nick who?” And I thought, that’s cool. She’d never heard of him.

You mentioned that when you were making Five Leaves Left, you were kind of modeling your production approach off of Leonard Cohen’s first album. That was interesting to me because I really don’t hear much of Leonard Cohen in anything Nick was doing.

No, no, I wouldn’t say that as singers or songwriters that there’s much similarity, I think it was more the production approach of John Simon. That idea of recording a voice not singing very loud, close mic, and the way that the strings are recorded, like a classical record more than a pop record, all those kinds of things. I think, definitely the girl’s voices in “Poor Boy” are very much inspired by “So Long Marianne”.

Yeah, that I can hear a little bit. When you first started work on The Roots Of Rhythm Remain did you have any idea that was eventually gonna end up being this like 800 page book? Did you have a thesis for it or was it just an exercise?

Well, I mean, I was definitely writing a book that was gonna have a beginning, a middle and an end, and end up in hardcover, I hoped. The structure and the content in the end was pretty much what I expected it to be, or what I aspired to have it be. What I didn’t think about at the start was the idea of it taking me 17 years [Laughs]. That was something that slowly emerged as an unpleasant surprise, that it was taking so long. I would start writing a certain section and say to my editor or my wife, “I’m gonna be done with this in another five months.” And then a year later I’m still working on it. But the structure, the basic idea was always that it would be about music that people knew what it sounded like, but didn’t know where it came from or didn’t know much about where it came from. There’s lots of music that has fantastic stories, characters, histories, etc, like Fado, or Rembetiko or Hawaiian music or Mexican music or whatever that I did not include in the book, and never intended to include in the book, because the book was about the hits. Everybody knows what a sitar sounds like. Everybody knows what Latin dancing is. Everybody knows what tango is. People know what Eastern European gypsy music is, or flamenco, but people don’t know much about where it comes from or who brought it to us. So that’s the shape and structure of the book is peeling back the layers of the stories of how that music that we know, that we’ve all heard, but don’t really know much about where it comes from.

I feel like one of the biggest points of contention regarding “world music” and things like that is this question of authenticity. Is that something that you think is important?

Well, no, I mean, I think every kind of music, whether it’s the most traditional or the most slickly packaged and produced, is a mixture. Music is part of culture. Take it at the most, you know, where the book starts, with the conflicts between the Zulu culture in South Africa and the Xhosa culture. One of the big differences between the Zulu language and culture and the Xhosa is the click. The Xhosa language has a very loud click. And the way Miriam Makeba used to sing “The Click Song,” you know, with those loud clicks all the time that I can’t even begin to imitate. But why do the Xhosa have more clicks than the Zulus? Why are the Xhosa clicks louder than the Zulus? Because they are geographically closer to the Saan people, normally known as Bushmen, and the Bushmen language is full of clicks. It’s all based on clicks. It’s click after click after click. And so, because they were positioned that way, the Xhosa people have more clicks. They learned that; it was absorbed. The same thing is true of every kind of music. The music is absorbed from whoever your neighbors are, whoever invades you, etc. It’s a historical process. Nothing is pure, everything is mixed. The idea that there can be some sort of purity in music is kind of ridiculous. But the question of authenticity is a modern concept. There’s definitely been a shift over the last 50 years that when music from another culture was presented in the so-called West, it had to be dressed up, it had to be polished, it had to be made nice. This is sort of the theory behind the Eastern European choirs and folklore companies. You had to make it choreographed. You had to choreograph the folk dances. You had to make everything in order to present a sophisticated face to the world. Now, the rougher and less polished and less overly smoothed out and arranged and choreographed something is, the better [it is] for a certain audience. That’s one of the tensions that I describe in the book is, for example, the Greek government went to great lengths in the ‘30s and the ‘40s and the ‘50s to try and stamp out Rembetiko because it was considered shamefully sexual and hashish-based, and Turkish-based. It was full of Turkish influences because it was being played by immigrants who’d fled Turkey in the early ‘20s, so the Greek government tried to stamp it out. Governments have always tried to do that, and cultural bodies have always tried to make things more polished, less authentic. But now authenticity, in many cases, for many audiences, is almost a fetish. The less polished something is, the more real it becomes. Which is a bit silly at times when it’s carried to extremes, but it’s also something that you see now spreading not just in music, but in tourism generally. People want an authentic experience. They want to go and spend two months cooking in a Calabrian kitchen to learn something real instead of just going to a fancy restaurant in Rome. People want to go backpacking off the beaten path. Young kids go for the summer to Laos, you know, they’re going to walk a trail up what used to be bombed by Henry Kissinger. So I don’t know what the word really means anymore, but certainly in musical terms, one of the themes of the book is that there is no pure music. Every culture’s music is influenced by historical migrations and contacts and overlappings and intermarriages. But since 1925, [it has been] hugely shaped by recorded music. And now with Spotify all bets are off, it’s all kind of a crazy mix.

I feel like I can see how different your approach is from someone like Alan Lomax, who seems very much like a purist about these kinds of things. A lot of my favorite record labels are labels like Ocora or Folkways that just present the music.

It’s ethnographic recording, a lot of that is documentary recording which, I have to say, as much as I do have a lot of Ocora and Folkways and stuff like that, I don’t listen to a lot of Ocora, or Folkways field recordings, I’m not that into field recordings. What I like is the performers who emerge from traditional backgrounds and become professionals and make records in proper studios and become stars in their local region or maybe even in their whole country, and who emerge to be something more than just authentic. I guess what I’m looking for is the golden mean - something which isn’t over-polished. I talk with some criticism in the book about what Miriam Makeba did when she came to America. Her first recordings and performances were very influenced by Harry Belafonte and this sort of polite folk style of the ‘50s, which he was a master at. She’d been sort of a township jazz singer in South Africa, she sang with the Manhattan Brothers. And she got to America, and she started to put on the folky Xhosa folk dress and walk out barefoot onto the stage and sing with somebody playing guitar behind her. In a way, she didn’t really have a hit record until she got with an R&B producer, and they remade “Pata Pata”. It had a bit of professional edge to it. I do find that in listening, for example, to old blues, that records that were pressed onto 78s and sold to the country blues market in the ‘20s and ‘30s have something that is lacking in field recordings. Maybe it’s quality, maybe sound quality. I mean, there’s some great Leadbelly records, of course, made by Alan Lomax and his father John Lomax, some of those records are great. There’s some fantastic records made in the field, but generally, it’s when - and I have this sneaking suspicion that has to do with getting paid - that when somebody says, “if we accept your record, your performance to be pressed onto a record, we’ll give you 25 bucks,” it’s a lot more interesting than somebody who comes to the microphone and says, “we’re here to document the folk music of the Mississippi Delta, please play your guitar.” But I don’t know, this is not a scientific theory.

I went to a dinner party in London once in the ‘80s, I think. Obviously I’d met Alan Lomax, we crossed paths a number of times, but he didn’t really remember me from Newport, you know. I found myself sitting next to him at this dinner - he’d had a few drinks, to be fair - and at one point we started talking about the process of recording and I told him a little bit about what I did and the kind of records I made. And I said, you know, in my view, it’s all just record producing. Some people are producing records for an academic audience - like you, Alan - and other people are producing records for more commercial audiences, like me. But it’s the same process. It’s just setting up the microphone, getting a performance out of the singer, and getting it down on tape or into whatever medium it’s going to be preserved on. He basically turned to me and he said, “step outside,” like, I’m going to deck you. [Laughs] And I didn’t, he’s bigger than me, but he took offense at the idea that there was a relationship between what a commercial record producer was doing, and what he, an academic ethnographer documentarian was doing. That there was the same process just for a different audience, he found that very offensive.

Was Alan Lomax ever a pleasant person to be around? Everything I’ve read about him just makes him sound like a huge dick.

Well, I don’t know. I never knew him that well. I’m quite good friends with Shirley Collins and she has a book about her time with Lomax and when she went with him all around the south, when he went collecting. She described some bad behavior on his part, but she adored him. And even looking back from later on in life, the way you might have a different view, you might say, “well, actually, looking back now, he was really a jerk.” But she doesn’t. She considers it a formative and wonderful experience she had traveling around the south. Although she then describes, sort of calmly, these situations where he obviously is acting like a jerk, she doesn’t see it that way. She just still has a warm spot in her heart for Alan Lomax. And she’s a wonderful person, she’s so sweet and lovely. So I don’t know the answer to that, because obviously, I never really got to know him very well. I mean, I’ve read The Land Where the Blues Began, parts of it are pretty boring but there’s some wonderful stuff in there. There’s some really great insights. Another thing that’s interesting about Alan Lomax, to his credit, is that his father, who helped get Leadbelly out of prison, recorded him and then persuaded the governor to pardon him or whatever. There was one of those paternalistic racist things going on, the governor was releasing Leadbelly into the hands of the Lomax family. There are these embarrassing films that you’ve probably seen of Leadbelly saying, “Yessir boss, I’m your man” and that kind of thing. At a certain point, Leadbelly got pissed off with the Lomaxes. He didn’t feel he was getting paid enough and didn’t feel that they were managing him well. He sort of ran off and set up on his own and started getting his own gigs and managing his own money and breaking free from the Lomaxes. Alan Lomax took Leadbelly’s side and basically encouraged him to do that and defended him to his father and they fell out badly over it and Alan defended him, so there are indications that there were certain situations where Alan had very good impulses and was on the right side, on the side of the angels. But yes, in general, my experiences with Alan have not been user friendly.

It seems like he was one of those people who was very admirable in certain ways, but also everything came with this intensity that’s probably common in music history. I’ve heard you mention John Fahey a few times, but I’m not sure what your relationship with him was. Was he someone that you knew?

I never met him. And I have to say, it’s a corner of music that I don’t have a lot of time for. The sort of noodley guitar that goes on and on, it’s just never appealed to me so much, that kind of guitar playing. But I know people who have very good taste that are devoted to Robbie Basho and John Fahey and different figures like that, but not me.

Yeah. I mean, I love Fahey and Basho, but the people who have come since then that get compared to him are people I usually just don’t care for. But I was curious about it because I feel like his attitudes towards the folk scene and people in that world are interesting to me, considering the things you’ve written about that.

I don’t know what his attitude is. I haven’t read interviews with Fahey, I don’t know much about him as a character.

I just know that he hated Pete Seeger’s music.

[Laughs] Yeah, I mean, I think Seeger is heroic. The thing about Seeger - not only is he politically and in so many ways heroic, but he was a fantastic musician. Have you ever heard The Goofing-Off Suite?

I have, I heard that when I interned at Smithsonian Folkways a few years ago. That’s a classic.

What’s your day job?

Right now I’m in grad school, trying to become a high school history teacher. Hopefully that will be my day job soon. Right now I’m just writing and doing things here and there.

We certainly need history teachers.

Absolutely. I mean, my interest in being a history teacher relates to a lot of the things that we’ve been talking about. I think realizing I was really interested in music history also made me realize that I’m interested in history in general.

Well, I mean, The Roots of Rhythm Remain in effect is actually a history book masquerading as a book about music.

Yeah. I mean the depth of historical knowledge and research that had to have gone into that book is really impressive to me. I know you went to Harvard, but you don’t seem to have an academic background.

I just read a lot. I’ve read a lot of history. I like history, you know.

I don’t want to ask too many more questions because we’ve been talking for a while, but I had a few more. You talk in White Bicycles about how this kind of rock revolution ended up elbowing out jazz and other kinds of music, because all the cool people and the rebellious people started gravitating to that instead of jazz. Something that’s interesting to me is that that was definitely a dynamic, but at the same time there were also these generational shifts going on with jazz itself. This intense evolution of swing to bebop and then to the avant-garde and everything else that came with it. This is kind of a long-winded question, but I guess given that history I was curious about your perspective on those generational rifts, considering that you’re someone who toured with Albert Ayler and you were also doing things with Coleman Hawkins and people like that.

You know, I’m hesitant to make too many pronouncements on that era of jazz because - I’m not sure if you read this part of The Roots of Rhythm Remain, but in talking about the influence of Indian music on Coltrane and the way that different feelings about scales and melodies came in from South Asia and how rhythms also came in and how, in a way, when Coltrane died, the flow of influence from Indian music into jazz that was coming through Coltrane passed in a way to a whole different sensibility to John McLaughlin and the complex rhythmic ideas of Shakti and McLaughlin and the Miles Davis bands that he was involved in and all this stuff which I never bought into, I never liked as much as the other strand of jazz. So I’m not the ideal person to talk about it because I didn’t really listen that closely to what was going on once Coltrane passed. I sort of drifted away from jazz. I could relate to Cecil Taylor and Albert Ayler and Archie Shepp and people like that more than I could relate to later Miles and Shakti and that kind of approach by the rapport. It just didn’t interest me so much so I don’t really have an eloquent statement to make on all that.

No worries. I know that you’ve released some classic records by Robert Wyatt on the Hannibal label and I know you talk about not being a huge fan of Soft Machine, so what about his solo music clicked with you in a way that the Soft Machine stuff didn’t?

Well, I loved Robert Wyatt from the beginning in Soft Machine. I loved his singing from the drum kit. There were three voices in the very early Soft Machine that played at UFO. The vocals were rotated between Kevin Ayers, Robert Wyatt, and Daevid Allen. And I could not stand Daevid Allen, I kind of tolerated Kevin Ayers, and I loved Robert Wyatt. That was my feeling about that group.

So you were probably happy when he went solo, I guess.

Well, I mean, that’s hard to say, because in a way his reason for going solo was that he fell out of a window and broke his back.

Right.

To gain a way of performing he had to learn a different way of presenting himself with a keyboard based approach. He’s wonderful. I think his health has been declining recently. I haven’t spoken to him in a while, but for a while we were quite friendly. He’s a great guy and a great force and a great spirit. I never really worked with him much except I did one single with Soft Machine, where he sang one side and Kevin sang the other side - Kevin or Daevid, I can’t remember. It wasn’t released, or it was released in Germany or something. I can’t remember. It eventually ended up on one of the compilations. That’s the only time I ever worked with Robert in the studio, but I was very happy to be a home for his records when he needed a home for his records, because I think the label that had released them before went out of business or something, so we released his archive.

I know you also released the Dagmar Krause Supply and Demand album on Hannibal, which I’m a big fan of.

I produced that one, yeah. It was a bit eccentric. It was a weird process because every song we did two versions, we did the German and the English version. We pressed an LP in German and one LP in English, but we couldn’t actually release it in America because the Kurt Weill estate wouldn’t let us. There were so many short songs, you needed a deal for the mechanical royalties, because America’s this barbaric country where the mechanical royalties are on a penny rate, as they say, like a fixed eight cents a tune or something like that. In Europe and everywhere else it’s a percentage of the wholesale price, so if you have 15 tracks on an album and another album has five tracks, in Europe they both get the same, you pay the same copyright royalty on both of them and the royalty is divided 15 ways on one and five ways on the other. In America you have a penny rate, so you have to negotiate with the publisher. If you have 15 or 20 tracks on a record, you have to get them to agree to give you a reduced rate so you can afford to put the record out. And The [Kurt] Weill Foundation was outraged that we hadn’t used their printed scores. We did - I thought - beautiful, wonderful arrangements based on the Kurt Weill arrangements. But some of the stuff was like part of an opera that you’re not allowed to perform unless it was using their scores. It was very bureaucratic and so the record never really took off, I was very sad about that.

That whole world of offbeat prog rock or pop music that I associate with Henry Cow or Slapp Happy, were those people who you knew and worked with a lot?

Well, funnily enough [laughs], there’s a story that I tell in White Bicycles. It’s kind of a long, weird side story, but I’ll try and compress it. Basically, I became very good friends with a German couple, Uwe Nettelbeck and his wife Petra. I then introduced them to Horst Schmolzi, who had been the one who almost signed Pink Floyd with me to Polydor in London. He signed Hendrix and he signed the Bee Gees and he signed Cream - [he signed] a lot of bands in a very short space of time to Polydor in London. And then the German Deutsche Grammophon, the parent company, got nervous and yanked him back to Hamburg. I introduced him to Uwe and Petra and he loved them. It was the closest he got in North Germany to the cool world of London that he had been living in for a few years. So he gave Uwe a deal to produce records and this all happened because of an accident where I introduced him to Uwe and Petra. Uwe had always wanted to produce records, but never had. He didn’t know anything, but he had a vision of doing it. And he persuaded Polydor to build a studio in his barn. That’s where he made the first Faust LP, the one with the transparent vinyl, and then Slapp Happy. And because he knew those guys in Hamburg, Uwe was the one who produced Faust and Slapp Happy and Tony Conrad. That all happened because of me, but I didn’t really have much to do with it. I knew Peter Blegvad and Dagmar [Krause] and Anthony [Moore] socially and I liked Dagmar’s idea of doing a cycle of Brecht songs so that’s how that record came out.

Yeah, that’s amazing. One question I forgot to ask about the UFO Club was about the film screenings you were doing there with works by like Jack Smith and Kenneth Anger and people like that. Obviously you went on to do film work for Warner Brothers, were you always as interested in film as you were with music or is it?

Not really. I mean, I thought that we showed Flaming Creatures just because some guy turned up at the door of the UFO Club one night with a can of film under his arm and said, ‘Do you want to do the British premiere of Flaming Creatures?’ We had a projector because we used to show WC Fields shorts at 3 a.m. and stuff like that. I’d never seen the film, but I had read about it in the Jonas Mekas column in the Village Voice. It was a sort of legendary underground film so I said, ‘Yeah, great.’ The next thing you know, Flaming Creatures is being projected onto the UFO screen, but it wasn’t anything that was organized or intentional.

Yeah, that makes sense. One thing I was wondering is are there any stories in White Bicycles that have been disputed by other people? I feel like when you’re remembering the ‘60s everyone seems to have a different perspective on everything that happened.

I can’t think of any offhand. I mean, certain little details have been corrected at times. I’m quite capable of blotting out somebody coming up to me after a reading and saying, ‘that was wrong, I was there, you were full of shit’, but I don’t think I’ve had any real serious disputes about my version of history. I think a lot of people argue about the ratio of boos to cheers at Newport ‘65, but for better or for worse - I did a long interview with the guy that wrote the book about Newport ‘65, Elijah Wald. Seeing the film, it seems that they took a lot of my version of the story as the basis, whether they got it from White Bicycles or they got it from Elijah Wald’s book, either way it’s my version of history. So, for better or for worse I keep telling these stories. People keep interviewing me and I keep telling the story my way. I think it’s true, I remember it that way, but other people might remember it differently. I guess I’ve done more talking so my version is kind of settling in as history.

I mean, I still don’t really understand how you’re able to remember all these different things that happened. I have a hard time remembering anything and I’ve had a much less busy adulthood.

Well, certainly talking about Newport ‘65, one thing that’s definitely true is that at the time everybody there felt that this is big, this is history. Nothing’s gonna be the same from now on. If you’re in a moment like that, you’re going to remember things. There’s a lot of details that definitely stick in the mind. Years went by and nobody was interested, nobody talked to me about it. And then starting in the late ‘90s or something, I started getting calls more often to go on the BBC and talk about Sandy Denny or go and talk to somebody about Dylan and I had this realization at some point that I wasn’t quite sure about whether my memory was of the event itself or of the last time I told the story of the event. I thought to myself, ‘shit, I better write this down or it’s getting farther away from the original experience, the original memory’. So I’m sure there’s some things that I’ve said that, when you start to compress certain things or streamline the narrative, the rough edges get sanded off a little bit and the story gets more straightforward. But I have pretty vivid memories of most of those things about those events that stick pretty clearly in my mind. But as I say, it’s certainly possible that other people would remember it differently.

Yeah, absolutely. I think this might be my last question. Towards the end of White Bicycles, you talked about how finding music on iTunes or whatever doesn’t really equate to the sense of discovery and connection you experienced in your day finding these old records with your friends. I can only imagine that that has been multiplied several times over since you wrote that now that we have Spotify and things like that and it’s as simple as clicking on music. Do you think there’s any way to retain that sense of discovery in this day and age?

I don’t know. Times change, everything changes, it’s the one constant we have so I don’t think you can ever regain the way things used to be. My only response is to try and have fun with it. My wife Andrea pointed out to me that you mentioned songs or whatever, in different interviews. We’ve done two 100 track long playlists in conjunction with the book. They’re both sitting on my website, but I can send you links to them.

Oh, absolutely.

You could listen to them. Those are basically just some of our favorite tracks from the book, some of the favorite artists.

I would love to see that. I have all my own thoughts and opinions about Spotify and streaming services and stuff like that, but that’s a whole other discussion.

From an artist point of view, it’s kind of a nightmare.

Yep.

But you can only deal with the world as you see it, and my function right now is to support people reading the book and enjoying the book and getting a vision of what the music sounded like that I’m describing in the book.

For me, I think the openness of the internet in terms of discovering music has a lot of pitfalls, but there’s also a lot of opportunities. I mean, talking specifically about streaming services, I think they’re terrible because obviously they don’t pay the artists, but also the algorithms are something I’ve always had a problem with. But again, that’s a whole other discussion.

I would just say that in this household we have our own algorithm which is called the alphabet [laughs] and I’ve loaded my collection bit by bit. I’m still scratching the surface. I’ve got lots of vinyl, lots of cassettes, lots of CDs. I’m loading the best stuff onto a hard drive and I’ve got an old fashioned iTunes program on another computer and we download onto a little iPod and listen in alphabetical order by song title so you get different versions of the same song, which is always interesting, but then you get something from Bosnia followed by a Mozart string quartet, followed by something from Memphis, followed by something from Hawaii, followed by something from Brazil, followed by something from Kentucky - it’s always a surprise. I never stop listening to music, it’s always a delight for me.

Oh, absolutely. Thank you so much for taking the time to talk. I mean, we’ve been talking for a long time now. Is there anything else that you wanted to mention before we end this?