An interview with Jim O'Rourke

I spent much of the summer this year working on an article for Bandcamp about Roland Kayn and the ongoing project releasing the late composer’s archival works. Ian Fenton, who runs the Finnish label Frozen Reeds, was kind enough to get me in touch with Jim O’Rourke, who has worked diligently on restoring the tapes of Kayn’s work for years. O’Rourke’s thirty-plus career in music has included a stint in Sonic Youth, bands such as Gastr Del Sol, engineering work for artists such as Wilco, Stereolab, and Smog, and frequent collaborations with luminaries such as Oren Ambarchi, Keiji Haino and Christian Fennesz. More recently, O’Rourke has been steadily expanding his set of experimental releases known as the Steamroom series, the 59th installment of which was released in November.

How are things in Japan?

Okay, I guess.

I heard there’s been an assassination recently.

[Laughs] Yeah. It seems to be bigger news around the world than it is here.

Really?

Well, I mean, politicians getting killed isn’t actually that shocking here. It happens quite a bit. But the method was unusual.

Let’s talk about Roland Kayn. Did you get to meet him at all while he was alive?

I never got to meet him, which is a real shame because I probably could have. But I never actually thought to bother him. When I was in college, I tried to find a way to switch to the university he taught at - give me a second, I’ve only had one cup of coffee - The Institute of Sonology. I applied for a study abroad thing but I wasn’t able to switch there. I might not have actually met him because he wasn’t actually teaching there. Up in the end he just had, like, an office job there, basically.

I was wondering if Kayn’s lack of acceptance from academic New Music circles resonated with you, since you’ve always seemed pretty uninterested in acceptance from academia.

I think my un-interest in academia is from going through it [laughs] and realizing the only thing I really learned from them was being forced into a situation where I had to learn how to articulate why I thought they were wrong. So it wasn’t directly an influence of Mr. Kayn. We may have had similar attitudes towards academia, but I didn’t know that about him at the time, because at that time it was very difficult to find out anything unless you talked to the person directly. There was ARPANET, but there wasn’t the internet [laughs].

Have you noticed any shift in recognition for his work now that it’s much more readily available?

I don’t know if I’m the best person to ask because now I’m sort of, like, disconnected from the real world [laughs] in that I’m not out there traveling and meeting people. But I mean, even back in the day, when the records were available, it really did seem like his music was known by the people in the know, if that’s the right phrase. Even the LP boxsets, by the mid-90s, were ridiculously expensive, and people weren’t able to share them over the internet or anything. And then, when he had the CD label, the CDs then became ridiculously expensive by CD standards. I mean, he didn’t do it, but for lack of a better way of saying it he was sort of priced out of the market, you know? [laughs]. I mean, I was lucky that I already had them. But in the mid-90s, for anyone who had heard about him or read about him to actually hear the stuff was really, really difficult. And outside of Barooni reissuing Tektra on CD in maybe about 95’ or so, you really couldn’t hear his music anywhere. And so, even for people already interested in him who wanted to know about him, he was sort of mythic. For all the new admirers of his work, of course, there’s not that problem, because, hell, you can just go listen to it for free on the Bandcamp page. You don’t even have to buy it to hear it. That aspect of his history is sort of lost, but he is still someone who has this sort of mythic quality about him, because there’s not a lot written about him, especially in English. I don’t think there’s a single interview of him in English. So just by the nature of how his work has been disseminated, and the lack of information, he becomes almost like a mythic figure. It’s as if he had done that on purpose, but I don’t think he did.

How did Tektra specifically have an impact on you?

Well, the thing I’m about to tell you isn’t necessarily what I thought. But when I first heard his stuff, I was in college. And you know, what composition professors teach you, especially in New Music and Classical Music, is that form is everything. And classical musicians and composers, they listen differently, they listen to the form. The form is thought of as a large overriding structure that is always forefront in the way that you listen. That was something that was being told constantly, but I didn't necessarily believe it. But when I first heard Tektra, it was the first thing that was a compelling argument against that way of thinking, because in the music in Tektra, the form is on a micro level. Everything is happening simultaneously and continuously. So his music was the first thing that showed me that there was another way of looking at this question. Of course, the obvious thing is that the music is just completely awesome. That’s the easy thing. It was like the Michelin-starred version of the Hafler Trio, and even Luigi Nono’s electronic stuff. This was, like, next-level awesome. But it wasn’t Parmegiani, and it wasn’t Luc Ferrari, it was complete abstraction. Which was another kind of shocking thing for me, because I was really into Luc Ferrari and Parmegiani. But that stuff is still interested in the ideas that can be expressed through representation. Kayn’s stuff had no interest in that whatsoever, the representation comes from the birth that you're witnessing in the act of listening. If you know what I mean.

I mean, in and of itself, that sounds awesome. But it’s interesting, because, as I’ll probably expose many times during this interview, I’m not really a musician…

That’s a good thing. Trust me.

[laughs] So I’ve heard. I’m not really knowledgeable about music theory or anything, but I can still notice in Parmegiani’s work, there’s a sense of dynamism, there’s shifts between different parts, almost like a non-electronic classical piece. Whereas with Roland Kayn, every sound element just flows into one another.

People like Parmegianni and Ferrari, as radical as they were, they were still basically rooted in traditional musical ideas. But Kayn really rejected that stuff. I mean, people who supposedly rejected those ideas, like Stockhausen for example, he would reject them using the same rules of the thing he was rejecting, you know what I mean? But Kayn really came from a completely different perspective, that was informed by ideas outside of music tradition. And he was lucky to have met Jaap Vink at the Institute of Sonology, who was the technician who made all these ideas that he had possible, who was also thinking outside of the traditional music history box, as it were. And that’s a testament to the strength of his work. You could go on for hours about, you know, the relation to music history, and this and that. But you don’t need to know about that or care about that because it’s not a conceptual thing, he actually makes it manifest in the work itself.

When I was reading about his work, I was thinking about John Cage and his ideas of challenging the traditional role of the composer and letting the sounds speak for themselves. But even he had his own rules and ideas of how music should be and what not, and Kayn’s work feels like a departure from that too.

I think in Kayn’s case, his situation probably affected it as well, because he wasn’t getting commissions, and he wasn’t really getting his music played. I think that allowed him to go places most composers couldn’t, because once composers become composers… I’ll make the point with a story. I really like Luigi Nono. And when I first got together with my partner, Eiko [Ishibashi], I was listening to some Nono. and at that time, she still hadn’t found a way into that particular period of avant-garde music. And I forget what piece I was playing, but she was saying “why do they always use this horrible soprano voice in their pieces.” Because that’s what the person who paid for the piece wanted! That’s an element of New Music that’s kind of lost on a lot of people. There’s this image that traditional composers are people who are in their room or whatever, writing whatever comes to mind - no, there’s a person who commissioned them to write a piece, or a group, and they have to write a piece for specific instrumentation, and that’s a big part of the music. That’s not meant as a criticism or anything, but that’s kind of a hidden element of why the music is what it is. If Kayn could get those commissions, I’m sure he would’ve been happy, I mean, I don’t know. But he wasn’t getting commissions like that, so he was just free to kind of do whatever he wanted to do, because nobody was nudging him in a different direction. You know, Cage, everything he did was a commission. That’s why there’s so many percussion pieces! [laughs] And cello pieces! Somebody asks them to write these pieces, they don’t just flow freely out of them. Because it’s their job. Well, it wasn’t Kayn’s job, because he didn’t have the opportunities. His job was working at a desk [laughs].

It’s funny, because when you’re talking about popular music, it’s almost a given that it’s never just the artists doing everything. Whether it’s the label or the producers, there’s always other people involved, but with composition people think those kinds of factors aren’t there.

Yeah, exactly, because the factors are so different. I mean, that’s the reason I became a recording engineer when I was in college. I noticed this. I’ve told this story a lot but it’s relevant here - I think my second or third year of college, when college would be out I would go over to Europe and basically live like a bum, but I was doing shows and already involved in things. And I came back for the next year, and my main composition professor says “so, what did you do during your break?” And I said “well, I went to Europe and I put out a record and I did this and that.” And he said “well, maybe you should take some time off to get these records and concerts out of the way so you can concentrate on your studies and get a teaching job.” That was a huge moment for me, because I was like “this guy’s fucking nuts.” And I realized at that moment I had to find a way to not rely on what I wanted to do to make a living, I had to do something else to pay the bills so that money would never come into the question of what I wanted to do. I already knew how to engineer because I was making tape music and stuff like that, but I started studying actual recording of other people and started doing it, and then for years that was how I paid the bills.

That’s crazy to me, because going to Europe and performing with all these legendary musicians on break from college makes it seem to me like you were getting the most out of your education!

Not to them, no. To him, I mean, he literally said that the end game is to get your doctorate, and while you’re getting your doctorate you get a teaching position, and then you get your students to play your music. Which is what he did!

Have there been any moments going through Kayn’s archive where you’ve found something that changes how you thought about his music? Or just general “holy shit, this is something else” moments?

Well, almost all of these pieces I’ve been working on, and the ones to remain, were all made in his home studio. So at that point he’s sort of doing megamixes really [laughs] because it’s not like he had the wall of modules that were at Sonology, or, for example, Leó Kupper’s GAME, he didn’t have these machines at home to work with. And there’s things in there that are surprising to me, because in the later things I don’t think he could really make new source material unless it was out of previously existing material. He’s basically working at home, he probably had two reel-to-reel machines, some filters, a mixing desk and a DAT machine. So the interesting thing is hearing how he constantly found new ways to use a very reduced amount of source material.

I wouldn’t have known that if you hadn’t told me.

And you know, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with it. It would be the same thing as complaining that the Ramones used a C chord [laughs]. Once you make something and it’s imbued with a meaning within one piece and becomes part of the self-created history of your work, referencing that has another meaning. It’s not using it, it’s referencing it, because it has baggage.

In your liner notes for Ákos Rózmann’s Images of the Dream and Death, you wrote that his day job as a church organist was an influence that couldn’t be ignored. Considering that Kayn originally studied organ at Stuttgart, I was wondering if you saw any connection between organ music and the kind of compositions that composers like Kayn and Rózmann were making.

Huh, I actually never thought about that before. I mean, I would think so because even on the sort of obvious level, with other instruments you change the tone color with your embouchure or your fingers, but with the organ you’ve actually got to move, you’ve got to stop playing to change the color. And that’s different than - gosh, that’s different than almost any instrument I can think of. It’s sort of [laughs] an industrial revolution kind of instrument. I mean, I don’t know how much that affected them, but that’s a very good point. Maybe it’s because of that mindset that they were attracted to the organ, or maybe it’s the organ that made them think differently about how they made music. I don’t know, but it’s quite possible.

There’s an old Mauricio Kagel piece - ugh, what’s it called…

Was it “Music for Renaissance Instruments”?

No, that’s a great piece though. It’s a pipe organ solo, I think the first recording was by David Tudor. There was a kind of famous organ record that David Tudor did on CBS Odyssey in the 60s, and there’s a Kagel piece on there that’s all just about pulling these stops out. It’s almost all about the stops and not what’s being played on the keyboard.

[some googling after the fact confirmed that the piece was “Improvisation ajoutée” from the 1968 LP A Second Wind for Organ]

Generally speaking, what would you say is your role in this project?

My involvement is cleaning up the tapes, basically. The choice of pieces and how they’re gonna be dealt with is done by Ilse, his daughter. A lot of his work, especially these later things were recorded using a consumer DAT machine in his home studio. They were considered state of the art when they first came out, you could record digitally on tape, but they were horribly unreliable, and that’s why they don’t exist anymore. But the consumer machines had this thing called long play mode, which was even less reliable. So when you get an error from a DAT machine, it’s not like tape, where something is overloaded and it’s fairly easy to fix. With a DAT machine, basically, the information is lost, so you have to interpolate where it begins to be lost and where it comes back. So a lot of the work is basically restoring these tapes. I think because he’s been in my life for so long, I understand the importance of dynamics in his work. So I think if these tapes were sent to a different person, and most likely a way better technical… sorry, I don’t speak english very often [laughs]... a much more technically proficient person than me…. I mean, I’m not a mastering engineer. And I never say I am, even though people write that anyway [laughs]. But the balance of my okay ability to do it with the fact that I know his work so well is the reason his daughter trusts me with this stuff. A different mastering engineer with better gear than me could have done it, but they would have compressed it. That’s the norm for how things are done in music now, but would be wrong for his music. The dynamic range is so obviously important in his work, and the fact of the matter is, the dynamic range he had to work with was less than what’s actually possible now. So you have to maintain that. But I mean, a lot of the work is just really getting the tapes back in shape. It’s Ilse who decides what pieces should come next, what should be on Bandcamp, the covers, etc. My role is mostly technical.

Has working on this archive been a continuous process since the A Little Electronic Milky Way of Sound box set?

Oh, it’s been non-stop. I have not had a break from it since Milky Way.

Have you been working on any of your own music in that time period, or have you been entirely focused on this?

Well, I do still work on my own music, but it’s much slower now [laughs]. I mean, really, I’m not exaggerating, I have not had a break from working on his stuff since Milky Way. Because from Milky Way, the Bandcamp things started immediately afterwards. And there’s the CD boxset work like Scanning and Tektra that happens simultaneously.

Are there any other artists you could imagine taking on this kind of endeavor for?

Well, I mean, I’ve always done this for Loren Connors. I mean, I don’t do all his stuff, but for years I was doing that for him, and anytime he asks me to, I do.

You mean mastering his records?

Yeah, or cleaning up tapes, getting things ready. I always help him, anytime. I mean, Roland Kayn’s in my top five music makers. Cecil Taylor and Derek Bailey, there’s plenty of people out there who will do that stuff for them, so they don’t need me, but I would do it for them as well, of course.

You mentioned Jaap Vink earlier. What was his role in Kayn’s music?

Technology-wise, a lot of the work came down to Jaap Vink and Leo Küpper. Especially the classic pieces by him, they really were a situation where Kayn was guiding how to create the source material, but the technical side of it, I think, really came down to Jaap Vink. Have you heard his music?

I have! I was gonna say earlier, I wish there was a similar kind of massive project related to him, because there’s just that one album on Editions GRM.

That’s all there is. Those are the only things he ever made.

That’s a bummer, because it’s incredible.

Yeah! [laughs] And he’s still alive.

Shit, I didn’t know that.

He’s 91 now.

That’s crazy.

And I want to make it clear that this is not a criticism of Mr. Kayn or anything. Again, it’s something that people don’t really think about with New Music, but that generation of tape composers, a lot of them had assistants doing the patching or the mixing or whatever, and the composers are like directors. And that’s an element of how that music was made. So I just wanted to give Mr. Vink his due.

Yeah, and that kind of relates to Miles Davis and the role Teo Macero played in putting together the tapes for his electric albums. There’s always several different moving parts, and all of it matters for the end product.

And you can hear it, if you listen to Jaap Vink’s work. Those are almost kind of like test runs of various techniques that he had to put together for Kayn or Leo Küpper. But the music is different.

You recently started doing a monthly program for NTS, and I was wondering how that came about.

Well, I mean, they asked me [laughs] and I said okay. It’s really that simple. I do a radio show in Japan that’s based out of a Kyoto radio station, and that’s like every second month every week. And basically, when that show is over, everything I played on those shows I put into one session and I make a collage out of them. So the NTS show is all collages, the Kyoto show is more track-track-track because in Japan, there’s really no radio show playing New Music or improvised music. So it’s really important for that show to introduce people to stuff that’s not being played on other radio shows. But for the NTS show, I treat it more like when I was doing radio in Chicago in the 80s. I was doing what they called free-form radio at WZRD, Northeastern University - I wasn’t a student there but I was a DJ there. I actually just finished the next mix yesterday, and that one actually turned out really good. That one’s really funny.

Really?

I was just slapping things on top of each other, and I was like “I was like “oh my god, is this in the same key?” I mean, everything just worked [laughs] so it was kind of amazing.

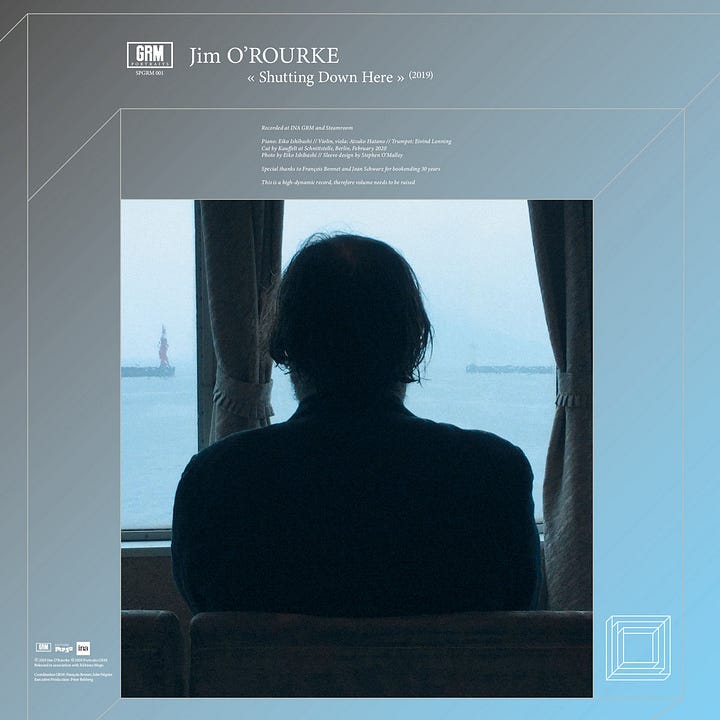

You said in an interview with Tone Glow a while back that Shutting Down Here was the closest any album came to being 100% of what you wanted it to be. It’s been two years since that album came out, and I was wondering if you still felt the same.

Yeah, it’s still maybe one of two things I’m happy with. I still feel okay with that one. It did what it needed to do.

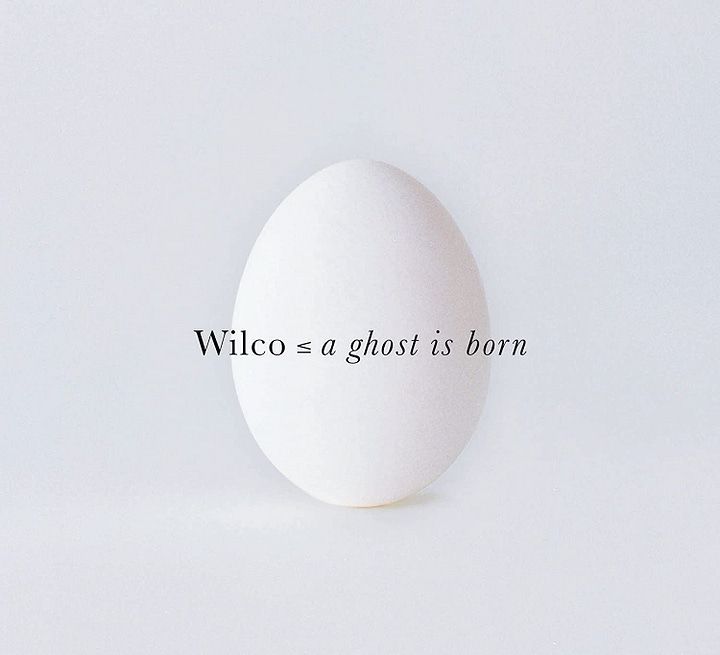

You also said that Wilco’s A Ghost Is Born was one of the records you worked on that you were happiest with. Why did that specific record really click for you?

Because it’s a good record, of course, but also because it was the absolute peak for me personally of producing a record the right way. I was involved before the recording, I was in the studio for the recording, every element of it was the best situation possible for me. It was sort of almost like finally doing that dream you have as a kid of being a record producer and the idea of how a record is made, for that record everything actually happened that way. And I know from being there that the record is the way it is because it would have been a different record if it wasn’t done that way. So yeah, I have really fond memories of making that record. I mean, I know for Jeff it wasn’t as easy. But for me, it was great [laughs].

Yeah, I guess that’s how it is.

That’s how the cookies crumbles. It was great for me [laughs].

In tandem, were there any Wilco records that went great for them that you were less happy with?

I mean, I wasn’t really involved after that. I did a mix of Sky Blue Sky but they used a different one. After that I haven’t worked with them since so I don’t know. When I moved to Japan I kind of stopped doing that work.

There was an album last year on Another Timbre, Best that you do this for me, that was composed by you and performed by Apartment House. Considering so much of your work is just you or you and a handful of close collaborators, I was curious as to how that project came about.

I was very grateful to get asked to write something for them. I mean, I don’t get asked that much. It was odd for me, because the score is open-ended in terms of how long you can play it. But for me, 10 minutes was fine [laughs]. They wanted to do it longer, and that’s their option. I think it might be the first record in which I had no involvement in any decision outside of writing the initial music. I wasn’t there for the recording, they made the decision to make it an hour. And none of that is criticism, it was out of my hands. Initially, I had no idea they were even going to record it. First, they contacted me about doing this thing I wrote, like, 32 years ago when I was in college, this string quartet and oscillators thing. So I had to find the score, which amazingly I did. I didn’t have to remake the tape part because I did it in Tokyo maybe 10, 8 or so years ago. So that’s just my first connection. I mean, the score is also something where they have to make a lot of decisions, although it’s very narrow with what kind of decisions they can make. I didn’t really have… I mean, that’s kind of where the title comes from [laughs]. But basically, the idea of passing on the responsibility to someone else is kind of unusual for me. And it’s not that I’m a control freak, it’s more the guilt of making someone else do something for me.

I wanted to ask about a few people you’ve collaborated with. I only just learned today that you played on one of Lawrence Butch Morris’s conductions.

Oh, that’s true! That was at a festival in Switzerland.

What was working with him like?

It was fine. You know, it was like two days, it was a rehearsal day and then the concert. I don’t even remember what I played… I think I may have played drumset? I didn’t get to spend that much time with him. Sadly, it was one of those things where it’s like “oh, I’ve gotta go play at this festival, oh, and because I’m gonna be there they’re asking me to play in this thing.” Sadly, it wasn’t anything more than that.

You did engineer work on Joanna Newsom’s Ys record, and Van Dyke Parks was also on that album. Have you worked with him at all outside of that record?

I’ve never worked with him. On that record, it was stuff that was all recorded before I was involved.

Have you met him at all?

I met him once when he came to Japan for Haruomi Hosono’s 60th birthday, 60 or 65th I think. It was a concert, and I got asked to do a song, and Hosono brought Van Dyke over from America. But I only met him for literally like two seconds.

What did you say, if you don’t mind me asking?

I don’t think I said anything. He said his daughter or his son knew my stuff and then he gave me this card he gives out to people, this greeting card, and that was it. I’ve emailed him a couple of times - I actually talked to him on the phone years and years ago. It was before Orange Crate Art came out. Henry Kaiser knew him from something and I was staying at Henry’s house. This is like 90’ or so, so I was like 21 or 22. And he’s like [imitates Kaiser] “yeah, I got this guy here who really likes you!” So I talked to him on the phone, and he sent me a cassette of Orange Crate Art that he was singing on - it was before Brian Wilson was involved. And sadly, I don’t have that cassette anymore.

I was asking because I had an experience where I met someone whose music I loved for two seconds. I graduated recently and at my commencement they were giving an honorary degree to George Lewis. He was sitting on the stage and when I was getting my diploma I just quickly said “hey, I’m a big fan!” and walked off.

[laughs] Yeah, he’s a really great guy. Do you know this book…

A Power Stronger Than Itself?

No, not that one. It’s this book about IRCAM, and there’s a huge section about George Lewis and his time at IRCAM. It’s really, really funny.

I think I’ve heard something about him having spent time there.

I can’t find the book but let me find the author’s name because she played bass in Henry Cow [laughs]. Her name’s Georgie Born. he book is actually quite boring because she’s an academe, and it’s some kind of nonsense academic thing, like, “an architectural history of IRCAM.” Whaaatever. And that’s not meant as an insult to Mrs. Born, it’s just academic books in general. The book is called Rationalizing Culture: IRCAM, Boulez, and the Institutionalization of the Avant Garde. The book is fascinating because she doesn’t use anybody’s real name. She uses pseudonyms, like it isn’t obvious who she’s talking about. But it’s worth getting that book just to read the section about George Lewis and his time there.

Trost Records recently reissued Xylophonen Virtuosen, your album with Mats Gustafsson. How did you two end up getting to know each other and collaborating?

Mats, I met at Company Week in 1990. So it’s because of Derek Bailey that I met Mats. And that’s why that record originally happened, because in 96’ or sometime around then, Derek started doing a guitar and sax series on Incus. So that was like John Oswald, Henry Kaiser, Derek and Alex Ward I believe, Zorn and Fred Frith. Then he asked Mats and me to do one, because we were kinda like “his kids.” He introduced us when I was like 21 and Mats was 23 or 22. So that originally came out on Incus as a CD.

I didn’t know it was on Incus.

It was originally on Incus, which was, like, amazing for me [laughs]. And Mats is even more of a record freak than I am, so for him it was almost like Mount Everest.

Did you participate in any of the group performances with Company, and were any of those recorded?

The duo I did with Eddie Prevost at Company got released on CD a long time ago. That should get reissued, now that I think about it. I don’t think anyone knows about that record. Yeah, there was a lot of things, but I know that it was recorded, and it’s kind of a bummer that stuff from that Company week never got released. I played a quartet with Louis Moholo, Thebi Lipere and Keith Rowe. It was like the guitar year. Usually Derek never invited guitarists, but that year he invited all the guitarists he knew [laughs].

Going off of Mats, you did an interview with him for his Diskaholics website where you said something about turning down offers to work with A-ha and the Rolling Stones? Was that true?

Yeah! The A-ha thing was basically just that I was going to be on tour, so I couldn’t do it. The Rolling Stones thing was some kind of weird thing, like there was going to be a roller coaster ride…

[I burst out into shrieking laughter] Sorry, I did not expect that.

I don’t know if it was a Rolling Stones-themed amusement park or what, but I remember specifically there was something for the roller coaster. Basically, they were asking people to do remixes of Stones songs - it was something off of Tattoo You. The guy who was in charge of this, he…. I don’t know, it got really weird. And I was like, “nah.”

It seems like it was weird from the beginning!

Yeah, it was weird from the beginning. And it’s not like I ever talked to anyone in the Rolling Stones, of course, it was some business guy. But eventually I did say “yeah, I don’t think I really want to do this,” but it was more because the guy was really freaky. Really kind of passive aggressive, I remember him yelling at me at one point, like, “I’m giving you the chance of a lifetime” nonsense.

“This is the fucking Rolling Stones roller coaster, most people would kill for this shit!”

Yeah, it was something like that.

I’m just picturing a roller coaster going through a giant tunnel shaped like Mick Jagger’s mouth.

I mean who knows, this guy who was talking to me, he might have been full of it. I mean, he was in the business, I know that. But you know, people in that world, they’re always running routines, so who knows. But the A-ha thing was literally just, I got the offer, it was a one minute call, I can’t do it, I’m on tour then.

In that same interview you said something about how you always wanted to learn pedal steel. I was wondering what attracted you to that instrument.

It’s my favorite instrument, I just love the sound of it. And it’s really difficult. I still can’t play it beyond basic. I haven’t even touched it in a few years [laughs].

Yeah, I have a friend who plays it and it seems like… a lot. Do you have any favorite players?

Well of course there’s like amazing, super technical people. I mean, it’s been a while since I’ve been on a real pedal steel kick. But I’ve always been very fond of Red Rhodes for the stuff he did in Michael Nesmith’s band. Especially Tantamount to Treason, which is a great, great, great record.

Yeah, I love Michael Nesmith.

There’s one tune on Tantamount to Treason, I think it’s called “You Are My One”? It’s just fantastic.

Do you listen to any of the people making more avant-garde stuff with pedal steel, like Susan Alcorn and Heather Leigh?

Not really, but I’ve liked Chas Smith for a long time.

Ah, I think I’ve heard you mention him before.

Back when I was in college, his first record Nakadai came out, and I was an enormous fan of that immediately. I actually don’t know his later stuff as much, I try to keep up with the stuff on Cold Blue but I actually don’t have all of it. But Nakadai is just a fantastic record, I’ve always loved that one.

I always get Chas Smith mixed up with Chad Smith.

This is totally a true story, very often at records stores like Disk Union here in Japan, the Chas Smith records get misfiled into the Red Hot Chili Peppers section.

Are there any record labels today where if you see that they put something new out, you’re immediately interested?

I don’t think I do that much anymore. I mean, there’s people that I buy everything from. But even ECM, I wouldn’t buy it just because it’s ECM. When I was younger I would, but I think it’s just that I’m at a point now where I don’t buy as many records as I used to. If it was me 10 years ago there would probably be labels I’d be following. I mean, there’s obviously a lot of great labels out there. Oren’s label is doing a lot of great stuff.

I love Black Truffle.

And, you know, Alga Marghen, although it doesn’t do too much any more, and Die Schachtel. But yeah, I guess I’m not buying that much stuff anymore. Oh, wait! There’s one label I want to, what’s the word, bump them? I want to send them a shout out, is that the correct word?

Yeah, that’s it.

Fundacja Słuchaj, it’s a Polish label that’s been putting out a lot of unreleased Cecil Taylor stuff. They sell the CDs on the Bandcamp page. Respiration, this one is fucking fantastic. This is so great, this is AMAZING. It’s a solo performance from 68’, which is a period that’s really not documented very much. It’s so good, it’s insane.

I feel like there’s been a lot of archival stuff of his coming out recently.

I do follow this label because they’ve been putting out these amazing Cecil records. They put out like four or five really great ones.

Cecil’s one of my heroes. I could listen to his stuff forever.

I mean, I’m wearing a Cecil Taylor T-shirt [laughs].

I know you’ve played with Tom Surgal before, did you see his free jazz documentary that recently came out, Fire Music?

I haven’t, I just got the DVD but I haven’t seen it yet.

I was in New York for a week about a year ago and the first thing I did when I got there was see it in theaters. It was really good, I enjoyed it a lot. Have you seen Imagine the Sound?

Oh, of course.

The footage of Cecil in that film is remarkable.

It’s fantastic. The funny thing is, I remember back when that came out it was only available on laserdisc [laughs]. I don’t know if it’s ever come out on DVD, I should check.

You get asked a lot what music you’re listening to or what movies you’re into at the moment, but I was wondering if you had any book recommendations.

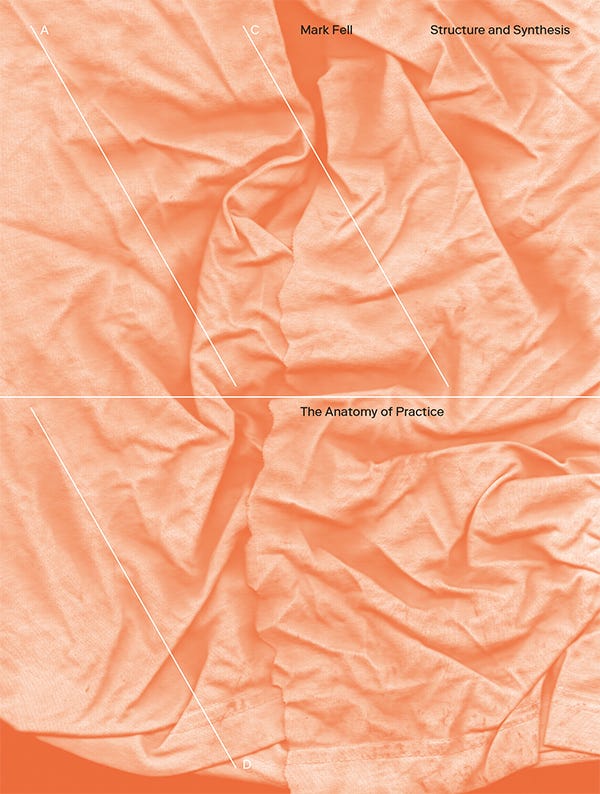

Mr. Mark Fell just put out a book called Structure and Synthesis: The Anatomy of Practice. I’ve only read the first chapter but it was very good. He’s a nice man.

Yeah, I love his music.

I just read Second Hypothesis by Rizwan Virk, which is okay. It’s interesting, it’s worth reading, but I think there’s probably a better book about the subject. Sorry, Mr. Virk.

I won’t tell him.

I’ve also been reading The Quantum Labyrinth, which is about Richard Feynman and John Wheeler. It’s mostly kind of a biography about their years working together. Yeah, that’s what I’ve been reading recently. I don’t read fiction, or anything like that [laughs]. It’s mostly just science books the past few years.

I don’t read too much fiction either, I love reading but I’m an incredibly slow reader.

Oh, well if you don’t read fiction I’ll suggest two fiction books [laughs]. Huysman’s Against Nature and Thomas Bernhard’s Lime Works.

I’ll check them out. I mostly just read books about music and history these days.

Okay, then I have a super suggestion. Do you know a music writer named Kyle Gann?

Yeah, I know about him.

There’s a book he wrote called New Music which is a collection of articles he wrote for Village Voice. But just a few days ago on his website, he put up scans of all of his articles for the Village Voice that weren’t in the book on his website. That is an absolute must-read. Just fantastic.