An Interview with Arnold Dreyblatt

When I talked with Arnold Dreyblatt at a coffee shop on the North Side of Chicago, ahead of a performance at Constellation in May, something that came up repeatedly was the idea of a life in the arts. Dreyblatt has certainly lived it; he studied media art with Steina and Woody Vasulka at a young age, and went on to study with almost every foundational figure in American experimental music (Pauline Oliveros, La Monte Young, Alvin Lucier and Morton Feldman, to name a few). He became fully entrenched in the fabled Downtown NYC scene, working with Arthur Russell and Phill Niblock and developing a singular mode of alternative tuning using beaten string instruments (which he dubbed “Excited Strings”) and rhythmic, pulse-driven compositions. Then, just as that scene was beginning to blow up, he left it all behind to move to Berlin, where he’s been based for 40 years now. His career has experienced multiple renaissances, from being rediscovered by a new generation of avant-minded record freaks such as Jim O’Rourke in the 90s to collaborating with bands such as Megafaun in the 2010s. The 2020s have been particularly fruitful for Dreyblatt, with a new wave of revelatory archival recordings and a brand-new release from a reinvigorated Orchestra of Excited Strings in 2023. Just a few days ago, a long-awaited collaboration with experimental rock masterminds Horse Lords was announced for release on November 21.

But what was most striking about speaking with Dreyblatt was how little he carries any of the pretensions that one would expect from such a life in the arts, speaking as a natural mensch above anything else. Dreyblatt certainly seems to have little interest in mystifying himself, and over the course of our hour-plus conversation he was willing to share every story he had, including witnessing Julius Eastman’s infamous June in Buffalo performance, attending a memorial service for Arthur Russell with Allen Ginsburg at Phill Niblock’s loft, releasing a tape he stole from La Monte Young, and much, much more.

Enormous thanks to Amelia for transcribing this interview. And, as always: PLAY THIS INTERVIEW LOUD.

Are you on tour right now, or is this just like a one-off thing?

It’s not really a tour. I mean, I basically came in for some family event - a 100th birthday.

Oh, ok.

And then I thought, since I was here, and people heard about it… I actually wanted to visit this friend I don’t see too often - I think it was seven years ago or six years - so yeah, this came up and then people heard about that,I have a thing in Buffalo at Hallswalls.

I don’t know if I know what that is.

It’s a very old institution. Art institution. So I’m giving a talk there about my work. I studied in Buffalo in the ‘70s.

Did you study with Morton Feldman?

Well, ok, I was a student in media studies so I have these two areas as an artist and as a musician. Woody and Steina Vasulka, early video artists - they founded The Kitchen - it was also an experimental film department and when I was there I started getting involved in the music department. I participated in June in Buffalo in ‘74, which was Pauline Oliveros and Joel Chadabe - I don’t know if you know who that is.

Yeah, I know him!

And also Feldman’s courses. We had kind of a connection because I was an outsider without a conservatory background and Morty knew my family from the garment business in New York.

Did he work in the garment business at some point?

He did until he got his first Guggenheim Fellowship, and he was proud of it. I have a lot of stories about that…Anyway, so he said he knew this grand-uncle of mine who had a factory where a Hollywood film was shot in the ‘50s with Kim Novak. I guess it was a big thing on the street in New York. So yeah, there was this connection. He said, okay you can come in and Pauline is probably good for you, y’know, because she’s an open composer. I often say she was my first real music teacher. I had done some things with electronic music before I came there, but yeah, it was a really intensive beginning. And the second June in Buffalo the next year was Cage, and that’s the famous one where Julius Eastman directed his assistants to undress during a performance of “Song Books.”

Oh wow, you were there for that?

Ok, you know about it. I was there in the audience as a very young person - how old was I in ‘75? I was 22.

What was it like witnessing that?

I remember a kind of embarrassment because it wasn’t only Cage and Feldman but they had invited that whole generation, y’know, Earle Brown and Christian Wolff, they were all there as far as I remember, so it was a dramatic moment, way ahead of its time in terms of coming out and making a very strong statement. Cage and a whole lot of that generation were gay but they never really spoke about it publicly. I was in the seminar the next day, I remember Cage being livid about it. Of course, he would say that, y’know, his ideas about music have nothing to do with those issues. I mean, the term ‘gender’ was not even in circulation at that time. I had actually almost forgotten about it until some kids from LA, from CalArts, contacted me. I don’t know when this was, maybe ten years ago. They had spoken to Ron Kuivila who had told them that maybe I was also there.

Were there any other young composers or musicians who were in that audience who later went on to do other things? I’m curious about that.

That’s a hard question. In fact - you know, when Ron Kuivila studied with [Alvin] Lucier together with Nic Collins, who is Chicago…

I have friends who have studied with Nic.

Right, right. I know you’re younger. So, [Ron] got the job after Alvin retired in Wesleyan. I did a second masters in Wesleyan some years later after I finished in Buffalo. I actually had been roommates with Ron when I was in Wesleyan years later, but we never talked about it, it never came up. I never knew that he was there. That’s the only way I can answer it. There were surely others. I mean, it was the, you know, all the composition classes, there was the Creative Associates in Buffalo, also very important at that time. Buffalo was actually a really interesting place culturally in that period.

I was going to say, the one thing I know about Buffalo in terms of its music and arts history is that it had that school that Feldman was teaching at.

But not only. So, it was in a couple of areas. The music department also invited through Creative Associates, they invited this kind of residency program for composers and for musicians so a lot of very important people of that period passed through. They also invited a lot of composers. It was a very intensive performance program at first. A very important moment for me was Alvin Lucier - who I didn’t know at that time, this was long before I studied with him - [He] presented in this very large concert hall, it was called Baird Hall at that time, with a stage that’s big enough for an orchestra. This is what I go into, ‘Music for Pure Waves, Bass Drums and Acoustic Pendulums’, something like that. It was basically just Lucier on one side of this enormous stage with an analog oscillator in the center of the stage, a snare drum and a loudspeaker on the ceiling facing diagonally down. It was actually a sweep oscillator so it’s starting from a low frequency and one of the things I learned later when I tried to realize this piece is that a lot of the drama of it is that analog oscillators at that time were very unstable so you had to kind of...you’re sweeping up and at a certain point, the drum started, the snare was released, it started sounding really loudly and you felt these frequencies, these standing waves going across the hall, like through your stomach. It was a really amazing, and for me, very important experience understanding that sound is really just the movement of molecules, and it’s invisible. Just really getting a sense of like a physical relation of sound and also triggering an instrument… I mean, there’s a lot of concepts that were later really important to me. I never forgot that. And it was from that that I started to work with sine waves and did a sine wave installation.

I was working in video then, that was my main work, but Woody Vasulka talked a lot about waves and waveforms and Chadabe was very good in explaining how sound audio technology works, audio synthesis and so forth in very simple terms, which is very important to me because I wasn’t coming from music. Literally, I think for me, the language of sound, the basis of where I began my music was in acoustics and the physics of sound. I didn’t have that cultural background. I only later learned how that relates to equal temperament and things like this and what instruments do. So, I think I realized at some point that when musicians are tuning, they’re actually comparing frequencies in their head. Subconsciously, I mean, without really thinking of it in that way. So, yeah, it really began then and at some point I moved out of video because I was working with frequencies, putting them into CRTs, like those old TVs that were a very different technology, an analog technology, and then I started to feel like the audio aspect was maybe more interesting than the images we were making. They were a little bit, for lack of a better word, kitschy. The seminal moment was at a party, a very drunken party at Hollis Frampton’s apartment in Buffalo. He was teaching film, a very important figure. I was sitting on a chair, and with interesting peers, I like to look at their bookcases, of course. I happened to see a bookcase right next to the chair and there I pulled out a copy of Selected Writings by La Monte Young, and I started looking at it and I realized, oh, this is maybe the key to it. How to move from analog electronics, signals, waveforms into music. Actually there’s an interview with Richard Kostelanetz printed in that book. It’s a very rare book published in Germany, actually, by Heiner Friedrich. I started reading that and he saw me really buried in this book and he just said, “Okay, you can take it.”

That’s incredible.

You can see I can go on and on. I love it.

So you started out with electronic music and then you moved into acoustics?

Well, I started in analog electronics. In a sense, it was the language of frequency and amplitude and modulation. I mean, it was the same in early video art, those were the concepts we were working with, those are the building blocks. So it was actually the same technology in the same language. I always say that I came into music through the language of first analog electronics and then, yeah, what I just said before: frequency, amplitude, understanding those basic concepts. And of course understanding how systems work in and out and plugging into things and stuff like that. In the early years I did a lot of research into musical acoustics. I didn’t have a basis for understanding instruments and, you know, quote on quote “music”. So it was like moving from sound installation into a desire to actually play music. That was a transition. It came through La Monte, of course, in a lot of respects he was a huge influence. That’s a whole other big chapter, complicated, but I still certainly grant him that. At some point, I want to have my own band and do it. So the question was “how do you do that?” So, I came back to New York, where I grew up before I went to Buffalo. Very soon after I came, there was a whole series of La Monte Young concerts at The Kitchen. I went there, walked up to him after, and I said, you know, Buffalo, blah, blah, I said some names. I didn’t know that he was looking for slaves [laughs]. So of course he said come over tomorrow. This is ‘75, I was a student in the sense that one is a student of La Monte. I think Rhys Chatham was the one before me. I lived over at the loft, partially, I worked for him and I had composition lessons, which was very interesting. Of course at some point there was the whole other political aspect. I realized how controlling he was. I won’t go into too much detail now publicly, but at some point, I said, I’m not gonna formally study with you anymore. I had been working on his tape library as an archivist and so I did that for another year. I actually tried to enlist Tony Conrad, at that point he was still loyal, but at a later point of course not. So yeah, I kind of moved more into Tony’s camp in terms of the politics of it.

Yeah, my understanding is that he had all these tapes that he wouldn’t release for whatever reason.

Yeah, it’s complex. Actually, there’s a letter I wrote to The Wire, which may be interesting to read.

I actually saw that.

That was my statement at the point that Day of Niagara came out, which I had actually stolen from La Monte at a time when I was concerned that nobody would ever hear this music. I copied it and gave it to Jim [O’Rourke] when I first came to Chicago. It eventually came out and people started writing me [asking] if I knew anything about it. That was my way to kind of come out and make a statement. I think what’s interesting there that I tried to talk about is the leader of an ensemble and the rights to the music and all those questions that come up.

You might have touched upon this already - What were the most important things you learned from this period of studying with people like La Monte or Alvin Lucier, all these really important composers?

That’s a big question. I often feel, you know, that I taught myself. For many years I taught in art school in Germany and I often told my students that so often contact with someone - the contact can be informal, it can almost be when I’m talking about an older artist or older composer, that the contact can be informal, it can be just a very short moment or it could be years of study - those moments give one a sense of a life in the arts, life in music. It’s not only the output, it’s also an example of a life in the arts, a life in music, which is often overlooked now because everything is moving so fast. Also possibilities of what one can do. It’s an inspiration to try to make something oneself. That’s even hard to talk about now, because the world has changed so much. I was also very close to Phill Niblock later until he died. He’s a very important figure for me. I once wrote, in the early days, I had my list of people I studied with and I put him in because he was so important to me and he got really angry because he said “I don’t have students”[laughs].

That’s an example of just being around someone who’s also an example setting an example. You have to also imagine a time before the internet, where everybody gets access to all information and can look up what everybody did. Those years, often people were really far away from those getting the right information or the information that you need. You would finally get to someone. That’s why I’m saying it often would be just a talk, a personal talk or being at a lecture.The extreme is actually studying with someone. I think those periods are really important.

I know Phill also came from more of a multimedia background than a musical background. Was that something you bonded over?

Yeah, I mean, it’s also interesting because he’s like 30 years older than me. I think we definitely bonded over that we both came out of the visual arts. We both had to figure out a way to do it. Phill had his own way, but we definitely had something in common, being autodidacts that just jumped in. People forget that Phill had a hard time in early years. He was not so accepted by the other composers of the scene in New York in earlier days and there were some difficult periods. He’s a hedgehog, you know, he’s a bear, he just moved forward, he didn’t care. But you know, that period late in life where he traveled nonstop and had generations of people around him, it took him a while to get to that, but he persisted.

Yeah, he definitely seems like someone who charted his own path and did things himself.

He’s also probably the most generous person I’ve ever met.

Yeah, that’s what I’ve heard from everyone who has met him. Obviously, he’s before my time, but it seems to me like he was very generous about supporting other musicians and giving them the space to do what they do.

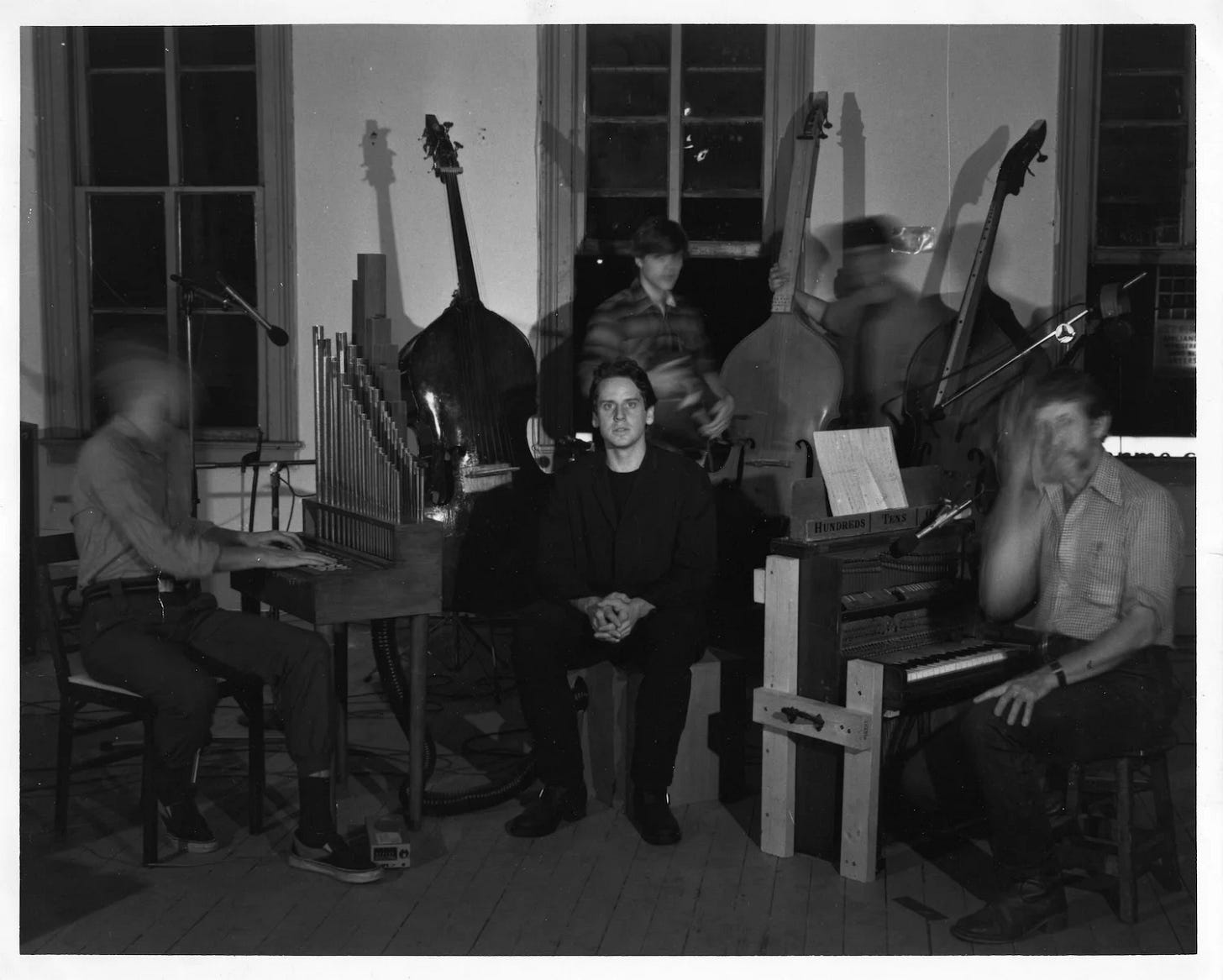

Yeah, he was very important to me when I was younger and then coming to New York, trying to get the thing going. I spent a lot of time with family somehow, or a surrogate family. He was even a bit of a surrogate father [laughs] telling me what I should do, you know. Don’t do that, do this, be careful. In the end he ended up having those roles for successive generations. There was also a strong feeling of admiration for each other’s work. It’s actually a kind of funny thing, but he was a little bit critical when I started doing my first music. The first band concert Orchestra of Excited Strings was at his loft, 1980, and my first solo performance was not there, but he helped support it and lent me equipment for it. He was anti-rhythm. That was a joke we had together because my music had rhythm from the beginning.

Going off of that, the rhythmic element of your music, it has more of an influence of rock music than a lot of your contemporaries. Were there any particular rock musicians or musicians in that sphere that particularly influenced your sound?

First I’d say I kind of missed my normal adolescence, but a lot of it was in the Fillmore East, you know, under the influence. You know, it was the late 60s, I was in high school in the early 70s. So it’s ridiculous, almost, to talk about this now, but of course, it was a part of a wave. One felt that this music, to some degree, also had political aspects. I heard a lot of rock music. There were, of course, some musicians moving from, I don’t know - we’re talking about very early ages, like 17, 18 - moving from the Grateful Dead and then suddenly starting to listen to John Coltrane and other musics. That transition, understanding that there was much more in trying to be open to other kinds of musics; world music, and so forth. They didn’t really even call it that then - Ethnographic music - that was a transition that I made quite early. But yeah, this rhythmic thing, I mean, it’s two aspects. One is what I just told you, and the other aspect is this hitting on a string, from this instrument that I adapted, which is the very beginning of my music, where it began, exciting the overtones on a single string that has a rhythm built into it so you’re striking it to generate this overtone. In a way, the whole music followed that.

It’s really fascinating to me, that time period where people were listening to rock music, but it also kind of fed into the interest in Coltrane and then the avant-garde and things like that. The way all those things were sort of connected is something I’m fascinated by.

Yeah, I mean, these were periods of like, Miles Davis playing at the Fillmore and stuff like that. I mean, it’s cliche, but even Ravi Shankar in the early days opened people up. You know, people had never heard music from other cultures, even if it was eventually appropriated in some way that now looks superficial. It still did make that possible. In a certain sense, I see The Wire that way, you know, in that it has articles on current bands or indie bands or whatever, but then there’ll be something about non-Western music and something about a composer of experimental music. Often it’s like, these are people I know, you know, music that I know, but it still opens it up to a larger audience so it has a positive effect.

It’s an interesting thing where people at that time were becoming more open and getting into the avant-garde through rock music, but it was also a time when some people were more closed off - I’m thinking about how Cage dismissed Henry Flynt’s music and his interest in folk and rhythm & blues and stuff like that.

That’s a whole other thing, because that generation, and Cage to some extent, and other famous composers that I won’t name, were no - I’m trying to think of a way to say it without going in the wrong - but there was definitely a rejection of popular music and, along with that, improvised music. Cage’s indeterminacy and structures for a kind of improvising formed parallel worlds that didn’t really meet. At least definitely from the composers, they were rejected completely. That’s kind of a sociopolitical aspect to the same thing.

You touched on it a little bit with Phill’s opposition to rhythm in music, but did you receive any pushback for incorporating these kinds of influences into your music from people in that world?

I want to say just about Phill that the irony of that is that he has a huge collection of jazz music from the ‘50s and ‘60s, and he was a photographer on a lot of sessions.

Yeah, I know he made that film about Sun Ra.

Yeah, but there’s many others, and he knows all the studios for Blue Note and all those labels, and he was present in a lot of those sessions, so he kept that. Sometimes I’d be over and he’d just start to put on his collection of recordings. But yes, I definitely felt that in the early years in New York - because for me also of course, I left New York at a very early stage. I was 30 when I left. Most of my adult life has been in Europe. I remember at that time sensing a bit of, I don’t know how to say it - maybe in the sense that non-classical musics or experimental musics were often rhythmical in some sense, that it was less serious in a way or that we shouldn’t do that or it’s pandering to public tastes or whatever. When I came to Europe I felt more free.

Actually, Arthur Russell was an important person that I met and became friends with shortly before I left, and he was also someone who said “just do it”. He actually put me in touch with a percussionist that he’d worked with at the time, I forget his first name. For the first time I started playing with a drummer accenting the rhythm, and when I came to Europe I just let that loose. There was a sense of being freed from that world. It’s hard to remember that period now, downtown New York. The scene was mostly academically trained composers who would come downtown to try and do other things, and me and Phill and a few others were still kind of outsiders. It was unusual, there were those who were starting to work with electronics, but I think it was important to have that other freedom I had when I left without any history and just do what I wanted to do. At least in my case it’s interesting looking at what happened, and it comes back to Chicago, like when I met Jim O’Rourke here in the 90s. Jim arranged a concert where we also played together at Lounge Ax, this is ‘96 or ‘95, and I remember being shocked that it was filled with hundreds of young people who didn’t need song form. That was a revolution, that they could listen to just sound. I couldn’t believe it. I remember saying to Jim, “Who are all these kids? Where did you dig them up?” I suddenly realized, oh, there’s a whole new wave coming, and of course, it has a lot of different aspects; computers, laptops, internet, techno, and all this stuff. Suddenly, a lot of the things that I was working with, there was large groups of people listening to it. I made a kind of unconscious decision at some time to move, because until then I was performing a lot in a contemporary music context, and suddenly, my music made much more sense in a kind of club scene, you know; amplified, rhythmical, loud. I still perform in both contexts, but that’s been a huge change.

Yeah, it’s an interesting thing - I get the impression your work is continually being rediscovered by new audiences, because first it was happening with Jim [O’Rourke] and the Table of the Elements scene in the ‘90s, and then with Megafaun in the 2010s, and now people like Horse Lords. I think it’s just interesting how it ebbs and flows with who’s listening to it, in a way.

Right, that’s absolutely true. That’s been inspiring. One of the things I found, like, there’s this aspect with tuning, I have a very particular tuning that I use since the very beginning of my music, based on the overtone series, but always with a fixed fundamental and not the relations of overtones to each other, always just related to the fundamental. Now, suddenly there’s a lot of young Americans in Berlin and they all know just intonation, and I think it came through software and the internet. You know, when I started nobody was interested in that. It was really very niche, kind of a crank area. Other than La Monte and Tony in that world, it was a very kind of weird academic corner of the music world, and now it’s part of the toolkit that young musicians have. But I notice when trying to work with some of these musicians and talking to them about it, it’s very different from how I use tuning, so they don’t relate to a fundamental in that way. Almost all music which deals with nuances of tuning in Asia, in the Middle East, have a reference to a fundamental. Either it’s there all the time, like a tampura, or it’s implied, but for them, it’s just different points somewhere that don’t necessarily relate to each other. With the Horse Lords I had that, I don’t want to say problem, but I had to explain it to them. I told them about that tuning system and then they could play all of it, it was incredible. For them it was just numbers, or like, positions, so I said I don’t play that note with that note because it doesn’t work together. So anyway, that’s interesting.

Do you see any differences between the musicians you were working with in the ‘80s, versus people like Oren Ambarchi, Konrad Sprenger, Horse Lords, etc?

In my own ensemble, the core of the ensemble is me and Konrad Sprenger and Joachim Schütz, and we’ve been working together since 2009, so that’s been continuous. Oren’s a good friend. Robin Hayward played microtonal tuba, and these are people who are actually the generation in between. Horse Lords, that’s the younger generation, they’re in their 40s and they have a lot of experience with this music and its different references. I should say that I work with a really important figure for me and a very close friend, Konrad Sprenger. We’ve worked together for many years because he also does studio work and he’s done a lot of the mixing for a lot of my records. We’ve collaborated for a long time, and now he has a name on his own, which is great. Jörg Hiller is his real name. We’re close friends and we’ve also, let’s say, co-influenced each other in various ways.

When you first moved to Berlin, who were the musicians you were working with or interacting with when you first got there?

Actually, it’s interesting that you ask that, because in fact, there were very few. When I came to Europe there was a lot of interest in the New York scene, you know, so when I came in ‘83 the first time - I moved in ‘84, but in ‘83 I was in Europe a large part of the year - and I passed through Berlin twice. There was a lot of interest in the New York scene, the New York minimalists, but there was very little in terms of a homegrown scene. It was like this exotic thing coming from outside, and the structures in Europe, especially in Germany or Switzerland, most of the countries were quite conservative, at least coming out of the conservatory. Really it’s only since - I don’t know how to term it, other than when I talked about Jim and that new scene that developed which I don’t really have a name for, a lot of people working with laptops, other kinds of music - that it became international. I guess it began in the late ‘90s. Now there’s a lot of people that I work with, but at that time it meant finding people who were willing to play with me and then to learn my whole thing, which was totally foreign to them. A person that I met when I first came, I don’t know if you know the name, Werner Durand.

Yes, I love his work.

We met very quickly when I came over. I’ve known him since my first days in Berlin. He played in the band for a period and he was someone with an unbelievable knowledge of music. Not only the whole contemporary music scene from the States, but also he had studied Indian music and was a collector of records. That’s a person who was also feeling isolated, because he also doesn’t come from a conservatory.

I wanted to ask about the Animal Magnetism album, because I feel like that one’s different from your other works. It feels like you’re working with a lot of instruments you don’t normally work with like horns and stuff like that. I know more recently you’ve been working with Robin Hayward and people like that, but with that album it felt different. Were you consciously trying to do something different with that album?

Interesting. Of course, yeah, I maybe see it a little bit differently because I know the whole history. The music on that record was actually developed for a theater piece that I did which was called Who’s Who In Central and Eastern Europe, 1933 that was based on a biographical dictionary; a lexicon. That was like ‘90, ‘91. Actually, Shelley Hirsch was in the original version singing with that music, and then finally made it to record with some changes. I’d already worked with brass when I was still in New York actually, that’s on Sound of One String, some of those pieces. Peter Zummo played on some pieces and some others. Brass works very well with the overtone series because they have to unlearn to compensate for temperament. That aspect, I would say, was not new, but yeah, there were some periods in the ‘90s where I experimented with writing more complex music.

That album definitely feels a lot busier than your other works.

And also rhythmically more complex, which is not easy for me. Of course computers helped, because I didn’t learn that, but just having more complex patterns playing, there’s that. Also, I don’t know if you’ve ever heard Adding Machine?

No, but I’m aware of it.

Yeah, that goes even further. That’s already from the 2000s, and actually on my website, there’s recordings from Tonic, which includes the live recordings from that which are much better, I think, than the record that I made. It happens sometimes, especially in those days. But yeah, the live recording is much better, but it’s also quite complex. There I worked with members of Bang On A Can, that’s a whole other part of my biography - Michael Gordon, especially, and Julia Wolfe were championing my music. They invited me to do things with the Bang On A Can Ensemble already in the ‘90s and I became friends with them. Of course, it’s also another world, you know. I did some pieces with them, and at that time I worked with some musicians from Bang On A Can with some additional contributions from Evan Ziporyn, who’s no longer involved with them but was at that time. He actually helped me arrange this whole thing and we also had some students from MIT. It was a great band, but more complex. I think with Konrad Sprenger, his influence was to get back to basics, which you hear on Resolve. Resolve really reflects the work that we did together since the early 2000s with the addition of Oren.

Obviously there’s a pretty large gap in between Appalachian Excitation and Resolve, were you trying to release music during that time?

Well, in another respect I was doing music all that time. I was surprised that suddenly all the reviews are saying “after 12 years”, you know, as if I didn’t exist.

Are you more drawn to live performance than recordings?

No, actually I have a backlog of live recordings I’d like to release if anybody’s interested. Also, I was performing a lot solo in that period. I did some other projects with other ensembles in Europe, in Stockholm, in Portugal, writing or doing a workshop and then developing a piece. I did a lot of those things, and a lot of that music hasn’t come out. I did more with some work with the installations. I was active the whole time, just no Orchestra of Excited Strings record came out in that time. There were other records that came out, but they weren’t Orchestra of Excited Strings. Also, I was involved in other aspects, so that it seems like a big distance, but it doesn’t seem so for me. And also, I should say that a lot of the music on the first side of Resolve is basically music that we’ve been playing since 2009. There was a failed attempt at recording this music in 2012 that nobody was happy with. We re-edited and re-edited for years until I said, look, we gotta just release it.

How did it change over time?

Well, it became more refined in some ways. Adding Oren was, of course, an interesting change. And actually, maybe to bring it up to the current day, the music that I’m performing tomorrow - the first piece is actually a pandemic piece. I have a new instrument, a different instrument. It’s also an Excited Strings bass, but it has a hard, solid body and it allows me to work with it horizontally or vertically, and it’s working with transducers on the instrument that I’m sending information from, modulating from Ableton with a lot of other material that I’ve developed. The first piece is a kind of interaction of the strings with electronics to some degree, and vibration. Then I do a short piece, which I’ve never performed in a solo situation, which is basically derived from that beginning of the second side from Resolve, which is me bowing harmonics, which works much better on this instrument that I’ve been developing. And then I do Nodal Excitation, you know, which is kind of a crazy thing, because there was a period where I stopped performing it, and then I realized that I really enjoy performing it and then a lot of people have never heard it live. It’s really hard to record Nodal Excitation, the solo, it’s just me hitting the bass.

Have you ever heard me live, by the way?

No, I’ll definitely be there tomorrow.

But yeah, there’s been this kind of steady stream of archival recordings coming out - a lot of them are Black Truffle - of important music from different periods. My collaboration with Paul Panhuysen, recordings from the ‘90s that haven’t come out, and also the collaboration with Tony and Jim. It was great that that came out. That was kind of revelatory for me.

I know that you’d performed with Jim previously, had you performed with both Jim and Tony?

No, never, it was the first time. It was actually put together by David Weinstein who used to be an old friend from New York. There was a certain aspect of it where it was really Jim and me fitting inside Tony’s world. I had been in some concert situations or tours alongside Tony and, of course, we’ve known each other since the early days. The connection is interesting because he came from La Monte, and then moved into film. “The Flicker” was of course incredibly important, but really very much based on those combinations of waveforms or repetitive structures and minimal structures, and in a way my music went the other way. You know, I’d talked to him about this in the old days, coming from this video, Vasulka idea of moving from waveforms into sound, in the other direction to some degree. But, yeah, he’s really important. As is my discovery of his influence on La Monte and the Archive.

I know you have an interest in the Archive as a concept, it seems to inform your visual art and works like that. Is that something that also informs your interest in preserving your own work, and keeping records of it?

Yeah, yeah, absolutely. When I mentioned this sense of a life in the arts, or life in music, it’s related to that. I’m in my early 70s, so, of course, you start to look back and try to chart those different directions.

I was gonna talk about The Kitchen, you said the Vasulkas were the founders, correct?

It’s Woody and Steina Vasulka, they worked together in most of the early years. There’s actually a big show now in Buffalo of Steina’s work. But yeah, they were both influential, but Woody, especially speaking about waveforms as a concept, definitely had a very strong influence on me. I have an interview with Steina Vasulka where she talks a lot about music and also founding The Kitchen. It’s interesting, you get a lot of history and she talks about the very early days of founding The Kitchen, and what it was like in New York at that time. Like, they didn’t have to pay rent [laughs].

Yeah, that’ll do it. It’s interesting that they were filmmakers, but with The Kitchen...

Well, Woody comes originally from music and then film. He’s from Czechoslovakia and Steina’s from Iceland and she was a violinist. They were among the generation of getting the first analog video equipment during the period of Nam June Paik, and others in the late ‘60s, early ‘70s. They were Europeans, they got the space and they just started inviting people to do stuff. She explains it very well in this interview.

How important were spaces like The Kitchen for developing your craft as an artist?

Not The Kitchen specifically, but that atmosphere in downtown New York at that time, there were a number of small spaces that one forgets how few people there were at these things. I was sometimes at important concerts where there were 30 people, it was a very small scene. I think one other aspect that’s not often talked about that I, to some degree, missed [is that] there was much more interaction between the different mediums. That was really also, I think, very important in my early years. There was often visual artists at concerts or theater performances. There was a feeling that, again, to use the term “wave”, in the late ‘60s, early ‘70s, everybody’s kind of part of the same wave but working in different areas. So there was a feeling of community and also that if you were doing one medium, it would be important to go see what other people are doing in other mediums. I was too young to witness, you know, like Judson Church and some of these main things in the ‘60s, but I definitely got the tail end of that. I was in the next generation and they were still active. At some point in the late ‘70s in New York, it split up. A lot of the visual artists all got famous and got their villas in Italy, and then it separated. But yeah, I think that’s something that’s missing now that everybody’s in their own world. I related to a larger world.

I’d read somewhere recently that they had avant-garde composers performing at places like CBGBs at one point in time.

Sure, like Arthur Russell. He asked me to come and play with him. The CBGBs performances were not on a, like a big night. They were not on Friday and Saturday nights, it’s the same as at Berghain. I performed at Berghain twice, but it also wasn’t on Friday or Saturday nights. There was a lot of that and also music performances in galleries. I performed in galleries and the audience was much more mixed, it was such a small world then. So, you know, you’d have people like Meredith Monk in the audience, and I don’t know, Phil Glass would be performing and there would be visual artists there. I remember performances in galleries, and it felt much more connected. It didn’t last very long. I don’t know if you know this, but I was involved in a number of big projects as an artist related to Black Mountain College, that is a bit of the legacy of that, which was totally interdisciplinary.

Yeah, absolutely. So you performed with Arthur?

Actually, I even took cello lessons with him, thinking I should maybe learn an instrument. We were doing it for a while and then he said, “You don’t really need to do this, just do your thing.” And yeah, I mean, it was a short period. I actually met him through Elodie Lauten. She died, unfortunately, but I lost contact with her and Boris Policeband.

Who?

Okay, there’s a name that really is off the radar. Boris Policeband.

Not sure if I’ve heard of him.

That’s something to look up, he’s someone that hasn’t been rediscovered yet [Editor’s note: he was in the band Jack Ruby]. And yeah, Arthur, I mean, there’s some statements from me in the Lawrence biography. I mean, he was really totally un-hierarchical. He was so incredibly open to all genres. There’s been a lot written about him. A very warm person who was very encouraging to me and I tried to be encouraging back.

Bobby Bielecki, who goes in another direction, built for me a tuning device where you could get any frequency in sine waves. It was digital at a time when there was almost no digital. I brought it over to Arthur and I heard that it influenced him to start playing in another way. I really liked his cello playing and I tried to encourage him. And then, of course, the connection to Phill- Phill really liked him also. I was very connected to Phill at the time that I met Arthur. I don’t remember exactly if I connected them in some way, I can’t really claim any credit for that, but it was definitely this other world. One of the times I came back from New York happened to be in the period that Arthur died and I remember there was an event at Phill Niblock’s for Arthur. And I remember one of the surprising things about it was there were all these different worlds that he was in. Allen Ginsberg was there, ‘cause he had performed with him and they were friends. They lived next door to each other. And then there was the gay club scene and dance scene, there was experimental music people. He had also studied with Ali Akbar Khan so there were Indian people there, and I remember Allen saying ”who are all these people?” Like, he had no idea that he was even known, he was just this young kid that he had performed with and they were friends. So everybody was like, well, who are they? And I think that really sums up Arthur in many respects. I really loved his singing and cello playing that he did at Phill’s. There was really something so beautiful about that.

Are there any recordings of you guys playing together?

We dabbled together, and I think the only time we played in public together was that time at CBGB. I should say that because there’s a bit of a confusion, there’s musicians that play with lots of different people, but I was always a band leader because what I actually do in playing this Excited Strings bass instrument is very limited. I don’t consider myself a musician that can play in all different contexts. So it’s not like I have an ax and I come together and play together. There’s so much of that in experimental music, especially among the young scene. I just don’t do that at all and when I’ve been coerced into doing that, I never feel comfortable. There’s been various situations where people said, “hey, you’re in Vienna at the same time, why don’t you come and play with us?” And, you know, I tried to do that and I just felt like an idiot [laughs].

But I feel like you’ve collaborated with a lot of people who seem to be kind of out of your comfort zone and you’ve made it work. I’m thinking of Megafaun.

Yeah. But you know, the Megafaun thing - unfortunately they didn’t last very long - but what was amazing about them is that their references were kind of folky stuff - you know, they had beards and all that - but actually they were totally informed. That was the thing that really was surprising to me. They knew everything about La Monte and Tony and all this stuff. One of them had a record store so they were totally informed. In a way it’s like you. How old are you?

I’m 25. [Editor’s note: I’m 26 as of the publishing of this interview]

You’re quite informed about everything. In a sense, for me, historically, like when I talked about the kids not needing song form, there were suddenly 200 kids at Lounge Ax that you could hear a needle being dropped, that’s what I felt. I thought, where the hell did they come from? And now you’re out of that legacy, because this didn’t exist before. I think people don’t realize how the contemporary music or whatever in the scene was so limited. It was a handful of people in New York, and outside even less. So in a way you’re an example.

I was talking about Henry Flynt earlier, there’s a passage in the David Grubbs book that mentions an interview he did with Kenneth Goldsmith in the 00s where Goldsmith was telling him that people of this generation will listen to experimental music and contemporary composition and also folk and rock, and won’t really delineate between different genres, and Flynt was like “what are you talking about?”

When I came to Chicago, that was the thing that totally shocked me. It was actually David and Jim who invited me, in fact, and I was shocked that for them, you know, a South Korean punk band was at the same level as John Cage. Not that many people came to Chicago then. It was just the very beginning of the internet. They knew most of what happened from collecting records. Jim had an enormous record collection. But, you know, it was an equal respect for all genres and that was completely new.

Going back to the Megafaun thing, do you think working with them brought like a folk music element to your music? Or do you think that was always present in what you were doing?

Yeah, I think it worked, they were really open musicians. I always felt an affinity to Appalachian folk music. I still love Appalachian fiddle playing and that kind of screechy music. My favorite record of all time is a Folkways record called Sacred Guitar & Violin Music of the Modern Aztecs, which is a trio of like violin and guitar and something else. It’s all carved out of trees and if you listen to it, you can hear a little bit of my music in it. You have to think of influence. Many people don’t want to say that influence works two ways: sometimes it’s more confirmation, like you hear something that confirms what you’re doing. And sometimes you’re directly influencing, absorbing some things that turn into something else. It goes both ways. I’m really big on that kind of Folkways type music.

I actually interned there a few years ago.

Oh, really?

Yeah. I’m from Washington, D.C.

DC was my first stop on this trip.

Oh, I didn’t realize that.

It’s now Smithsonian, right?

Yeah, it’s owned by the Smithsonian.

Moses Asch is kind of an interesting figure, yeah. He’s the son of Sholem Asch.

I think I knew his dad was somewhat important, but what did he do again?

I think he was a Yiddish writer or something like that, and publisher. It’s an interesting background.

I have one last question, I was curious about your work with Chico Mello.

Oh, you know who Chico Mello is?

Yeah, he’s great. He also had something on Black Truffle, right?

Right. They re-released that early record. He played in the band for a period.

I read that somewhere, which is what made me curious.

It was actually two Brazilians, Chico and Silvia Ocougne. That was in the ‘90s, I think Silvia brought in Chico. I still see him occasionally in Berlin. We don’t see each other that often, but it’s always very friendly. Quite an interesting composer. It goes back to when you asked me about finding musicians to play at that time. The two Brazilians, they grew up also playing Brazilian folk pop stuff and were used to other genres. Rhythmically they were very interesting, so it definitely brought something into the music, and it was really nice working with him. He was somebody I always felt guilty about because he really wanted to compose every day and we’d have these rehearsals and it was always an interruption for him. But yeah, wonderful guy, interesting composer. He studied with a quite well known German composer who was based in Berlin who died recently - [his name will] come to me as soon as I leave you.

[laughs] That’s often how it goes.